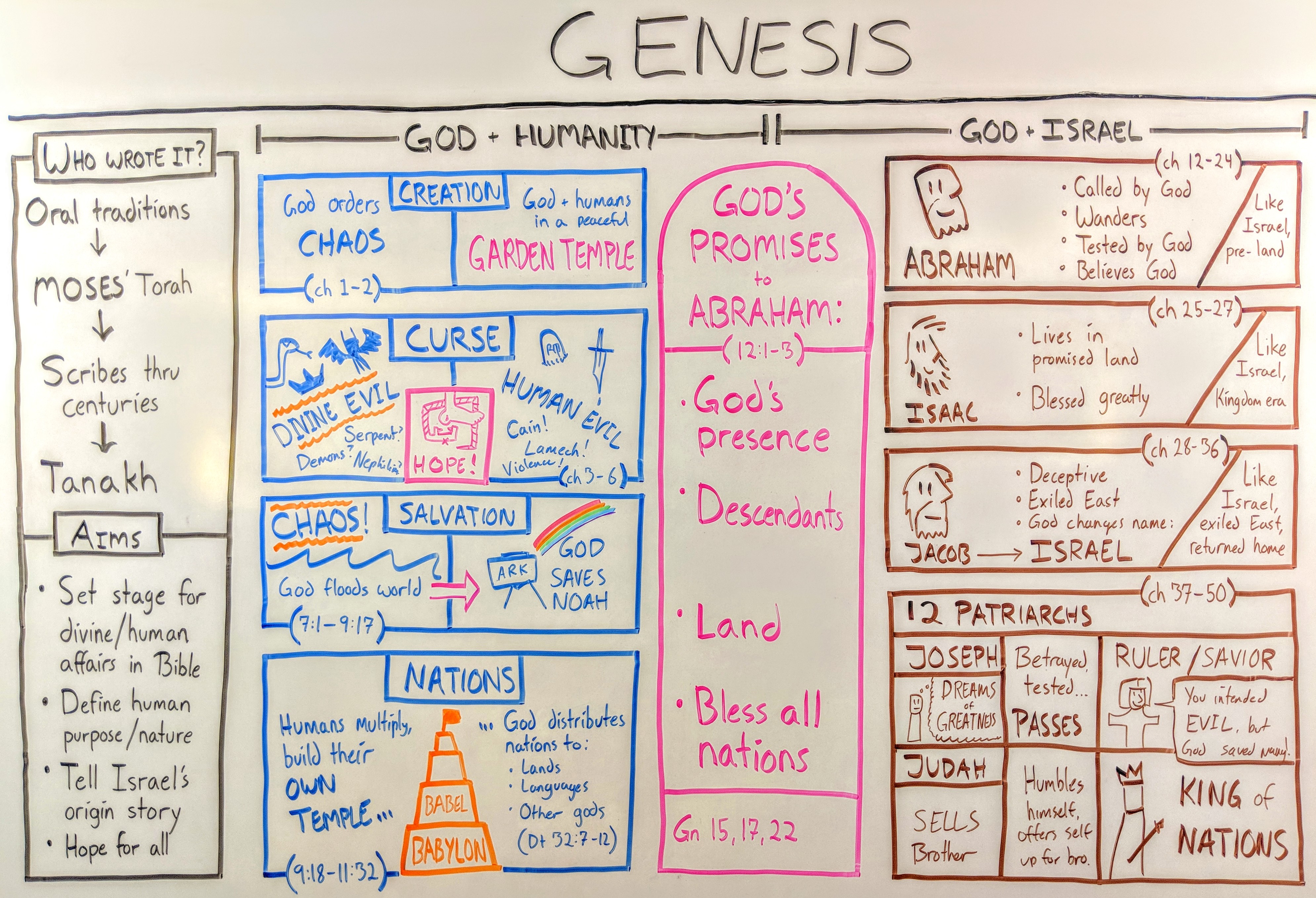

The book of Genesis is the first book of the Bible, and opens with one of the most famous first sentences of any literary work: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” It’s where we find the famous stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and the ark, Abraham and Isaac, and a well-dressed dreamer named Joseph.

On its own, the book of Genesis reads like a string of epic stories: a semi-tragic saga of a world that just keeps going wrong, despite its Creator’s intentions. But Genesis isn’t a stand-alone book. It’s the first installment in the five-part Torah (or Pentateuch), which is the foundational work of the Old Testament. The Torah is Israel’s origin story: it’s the history of how the nation of Israel got its population, its land, and its religion.

Important characters in Genesis

Genesis is the second-longest book of the Bible (after Jeremiah). That means there are a lot of characters in Genesis. If you want a look at the most-mentioned characters in Genesis, Adrien pulled the nerdy data together here. But in terms of getting an overview of the book, these four characters are the most important ones to know about:

God (Yahweh)—the creator of heaven and earth, including the humans Adam and Eve. God makes all things “very good,” but when both humans and divine beings rebel against God, the world slips back into chaos. The humans rebel against God, bringing a curse on the world and growing so violent that God destroys everyone but Noah and his family. God is still at work to bring the world back to “very good” status again—and chooses to begin this work through a man God names Abraham.

Abraham (formerly Abram)—a Mesopotamian whom God chooses as the patriarch of a special nation. Abraham journeys through the land of Canaan, which God promises to give to Abraham’s descendants. God makes a covenant (a special binding agreement) with Abraham—which is where Israel’s story as a nation truly begins.

Jacob/Israel—Abraham’s grandson. Jacob tricks his father and brother, finagling his way into receiving a special blessing. He has twelve sons, which the twelve tribes of Israel trace their lineage back to.

Joseph—Jacob’s favorite son, who has prophetic dreams of greatness. He is also able to interpret other people’s dreams. His brothers sell him into slavery, but through his God-given wisdom, he ascends to the position of second-in-command over all Egypt.

Key themes in Genesis

The book of Genesis is full of stories we know from Sunday school, like Adam and Eve, Noah’s Ark, and Jacob’s Ladder. But the story of Genesis is really all about setting the stage for the rest of the Pentateuch: it’s the long, long prologue to Israel’s beginnings as a nation. Specifically, it’s the story of the promises God made to humans—promises that God begins to carry out through the rest of the Bible.

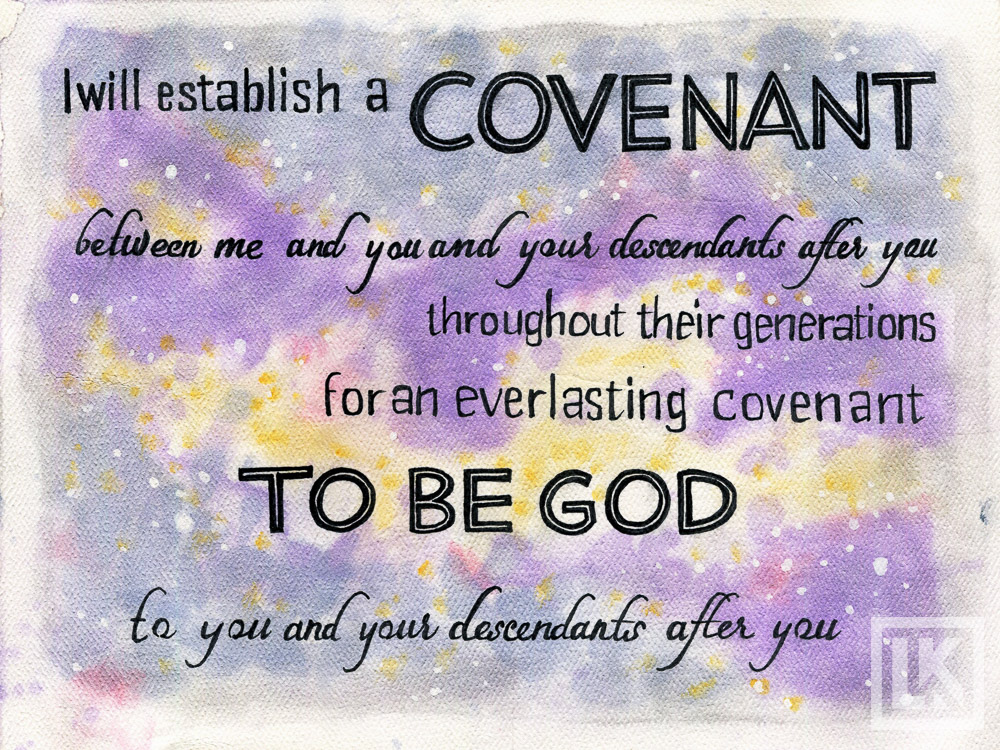

In fact, if the main thrust of Genesis were summed up in one verse, it would be these words that God said to Abraham:

I will establish my covenant as an everlasting covenant between me and you and your descendants after you for the generations to come, to be your God and the God of your descendants after you. (Gn 17:7, NIV)

See Bible verse art for each of the other books of the Bible.

Let’s take a quick tour of Genesis’ foundational themes:

Covenant

A covenant is a solemn, binding agreement that makes two or more parties one (you can get a more in-depth definition here). Covenants usually involve promises, conditions, blessings for keeping the covenant, and curses for breaking it. Genesis has a lot of these agreements, including God’s covenant with the post-flood world (Genesis 9:1–17) and his covenants with Abraham (Genesis 15, 17).

Covenant is what moves the story forward in Genesis. God promises the childless Abraham that he will be the father of nations, that his descendants will have a land, and that the world will be blessed through them. For 38 of Genesis’ 50 chapters, the story follows Abraham’s family as God begins fulfilling the first part of that promise: Abraham has eight children, who have children of their own, and so on and so forth. The next four books tell the story of how these descendants become a nation and make their move toward claiming their promised land.

As you read or study the book of Genesis, pay special attention to any mentions of “covenant,” “promise,” and “swear”—especially when God’s the one talking.

Blessing

In the twelfth chapter, God promises to bless Abraham, bless his allies, curse his enemies, and eventually, bless the world through him (12:1–3). This kicks the rest of the book, the rest of the Torah, and indeed the rest of the Bible into gear. From this point on, God has a special relationship with Abraham and his family. The rest of Genesis watches this promise unfold—and it involves a lot of people getting blessed.

The narrative of blessings is especially important when we get about halfway through the book, when Jacob “inherits” (i.e., tricks his dad into giving him) the blessing that God had given to Abraham and Isaac. This blessing was originally intended for Jacob’s older brother Esau. But before another Cain and Abel situation takes place, Jacob escapes to a distant land, where he starts a new life. When Jacob returns, he wrestles with God—who blesses him.

As you read and study Genesis, keep an eye on who blesses whom, and what happens when people are blessed.

Records and genealogies

A key repeated phrase in Genesis is, “this is the account of …,” or “these are the records of…,” followed by either a bunch of names or a bunch of stories. In fact, this is pretty much all of Genesis. The second chapter opens with the account of the “heavens and the earth,” (2:4). Then the book of Genesis swings us through a long series of sub-accounts:

- Adam’s family line (5:1)

- Noah’s family line (6:9)

- The nations that stemmed from Noah’s sons (10:1)

- Abraham’s family (11:27)

- Ishmael’s family (25:12)

- Isaac’s family (25:19)

- Esau’s family (36:1)

- And finally, Jacob’s family (37:2)

As you read through Genesis, pay attention to these lines—they signal that the focus of the book is shifting from one family to another. Genesis is a collection of origin stories—these genealogies feel trivial to modern readers, but they give us a good idea of how the ancient Israelites thought about the countries surrounding them.

For example, the nations of Israel and Edom don’t tend to get along in Scripture. (There’s an entire book of the Bible about how Edom did Israel dirty.) Genesis frames this rivalry: they’ve been getting each other’s goats since Jacob stole Esau’s blessing!

Promised land

One more important theme in Genesis: the land of Canaan. God promises that Abraham’s descendants will possess that land in chapter 15, but this promise is not fulfilled until the book of Joshua. Abraham wanders through Canaan, Isaac settles there, and Jacob eventually settles here, too. However, at the end of the book, the budding nation of Israel is dwelling as guests in Egypt. The next four books of the Torah tell us how they make their way back to Canaan.

As you read and study Genesis, don’t just pay attention to what is happening—pay attention to where it’s happening.

Zooming out: Genesis in context

Genesis is the first book of the Bible, but more importantly, it’s the first book of the Torah, the law of Moses. Genesis told the ancient Israelites that God had befriended their ancestors, promised them a land, and had a plan to bless the world through them. But the story of Genesis is really just the grand prologue to Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Together, these five books tell the story of how Israel became God’s special nation.

Genesis ends with Israel in Egypt as special guests. But Exodus begins with Israel being enslaved by their hosts. Through the rest of the Torah, God rescues Israel from Egypt, declares them to be his people, and leads them through the wilderness to their promised land. Genesis explains how Israel came to be in Egypt in the first place, and why, of all the places on earth, God lead the nation of Israel to that patch of land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

If we look beyond the Torah (and we should!), the stories in Genesis set the backdrop for vital theological principles in the rest of the Bible. In Genesis, we see that God has authority over the world. We see that humans and other creatures (like the serpent and the Nephilim) are in rebellion against God’s order. We see the hints of God’s plan to redeem his creation back to himself.

Genesis also introduces Abraham, the ancestor of Israel through whom the whole world will be blessed. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are the three chief patriarchs of the nation Israel (which gets its name from Jacob). Jacob’s sons and grandsons have their own families, which eventually become the 12 tribes of Israel.

Abraham believes God’s promises to him, and Abraham’s faith is reckoned to be righteousness (Gn 15:6)—that is, it satisfies God. The concept of righteousness by faith is repeated in the New Testament (Ro 10:10), and Paul states that all who share Abraham’s faith are the spiritual children on Abraham (Ga 3:6–9).

Genesis sets forth several biblical themes that weave across the rest of the Bible:

- God’s authority. God is the maker of all things, and He is sovereign over nature and humanity. We see His creative work in the first two chapters of Genesis, but we also see His sovereignty in choosing Abraham, blessing the Hebrews, and protecting Egypt from famine.

- Man’s rebellion. Adam and Eve disobeyed God in Eden, but that’s only the beginning. Cain presents an unacceptable sacrifice, the world becomes violent in the days of Noah, people construct the tower of Babel, and so on and so forth.

- God’s judgment. God evicts Adam and Eve, He sends a flood to destroy the earth, and He rains fire on Sodom and Gomorrah (Gn 19). God is holy, and sin must be punished.

- God’s preservation of life. God promises a descendant to Eve (Gn 3:15), He saves Noah’s family in an ark, He delivers Jacob from Esau’s wrath, and He allows Egypt to survive a harsh famine through Joseph’s wisdom.

- Blood sacrifice. God skins animals to cover Adam and Eve after they sin (Gn 3:21), and He provides a ram for Abraham to take Isaac’s place (Gn 22). The blood sacrifice motif becomes far more prominent in the book of Leviticus.

It’s a grand book with many of the Bible’s most well-known stories, but it’s only the beginning.

Overview of Genesis’s story and structure

Genesis can generally be broken into two large movements, each one the beginning of a bigger story. The first is the story of God’s relationship with the world. The second is the origin story of God’s relationship with Israel.

Movement 1: God and humanity

(Genesis 1–11)

Genesis opens with God creating the heavens and the earth, the stars, the plants, the animals, and humans: Adam and Eve. God places Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, but they rebel against God, introducing a curse of sin and death to the world.

Adam and Eve have children (including Cain and Abel), and those children have children. Eventually the world becomes so violent that God sends a great flood to destroy the world, but He spares the only righteous man, Noah. Noah builds his famous ark to escape the floodwaters with his family (and many animals). After the waters recede, God promises to never again destroy the earth with a flood.

This movement culminates with the strange story of the Tower of Babel. The people of earth come together to make a great city and a name for themselves. At this time, God and the divine beings with him scatter the people of earth by confusing their languages and setting up different nations (Genesis 11, Deuteronomy 32:8).

Movement 2: God and Israel

Act 1: Abraham & Isaac

(Genesis 12–24)

Hundreds of years later, God calls Noah’s descendant, Abram, to leave his family and journey to the land of Canaan. God promises to bless Abram with many descendants, and to bless all the nations of the world through him. Abram believes God’s promise, even though he is old and childless. God considers him to be righteous, and changes his name from Abram to Abraham. Later, Abraham has a son, Isaac.

Act 2: Isaac

(Genesis 25–27)

Isaac dwells in the land of Canaan and has twin sons: Jacob and Esau.

Jacob grows up, tricks Esau into giving away his blessing, and Esau’s not too happy about this. So …

Act 3: Jacob/Israel

(Genesis 28–36)

Jacob then leaves town to live with his uncle. He marries, has 13 children, and lives with his uncle for 20 years before God calls him back to Canaan. As Jacob returns to the land of Abraham and Isaac, his name is changed to Israel (35:9–12).

Act 4: Joseph

(Genesis 37–50)

Of Jacob’s 12 sons and one daughter, Joseph is his favorite. Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery, and he becomes a prisoner in Egypt. His God-given ability to interpret dreams becomes valuable to the Pharaoh, however, and so Joseph is released from prison and made second in command of all Egypt. Joseph warns Pharaoh that a terrible famine is coming, and stockpiles food for the coming years.

Joseph’s predictions are correct: the famine reaches Canaan, and his brothers come to Egypt to buy food. The brothers reconcile, and Joseph provides for all the children of Israel to move to Egypt until the famine is over. The book of Genesis ends with the death of Joseph, whose last prediction is that God will bring the children of Israel back to the promised land. God begins fulfilling this in the next movement of the story: the book of Exodus.

Who wrote the book of Genesis?

Genesis is a carefully and intentionally crafted account of Israel’s origin story. Moses is traditionally credited as the human author of the Old-Testament book of Genesis. This is because Genesis is part of the Torah, which is known as the Law of Moses.

Pages related to Genesis:

- Exodus (next book of the Bible)

- Leviticus

- Numbers

- Deuteronomy

- Galatians (lots of discussion on Abraham)