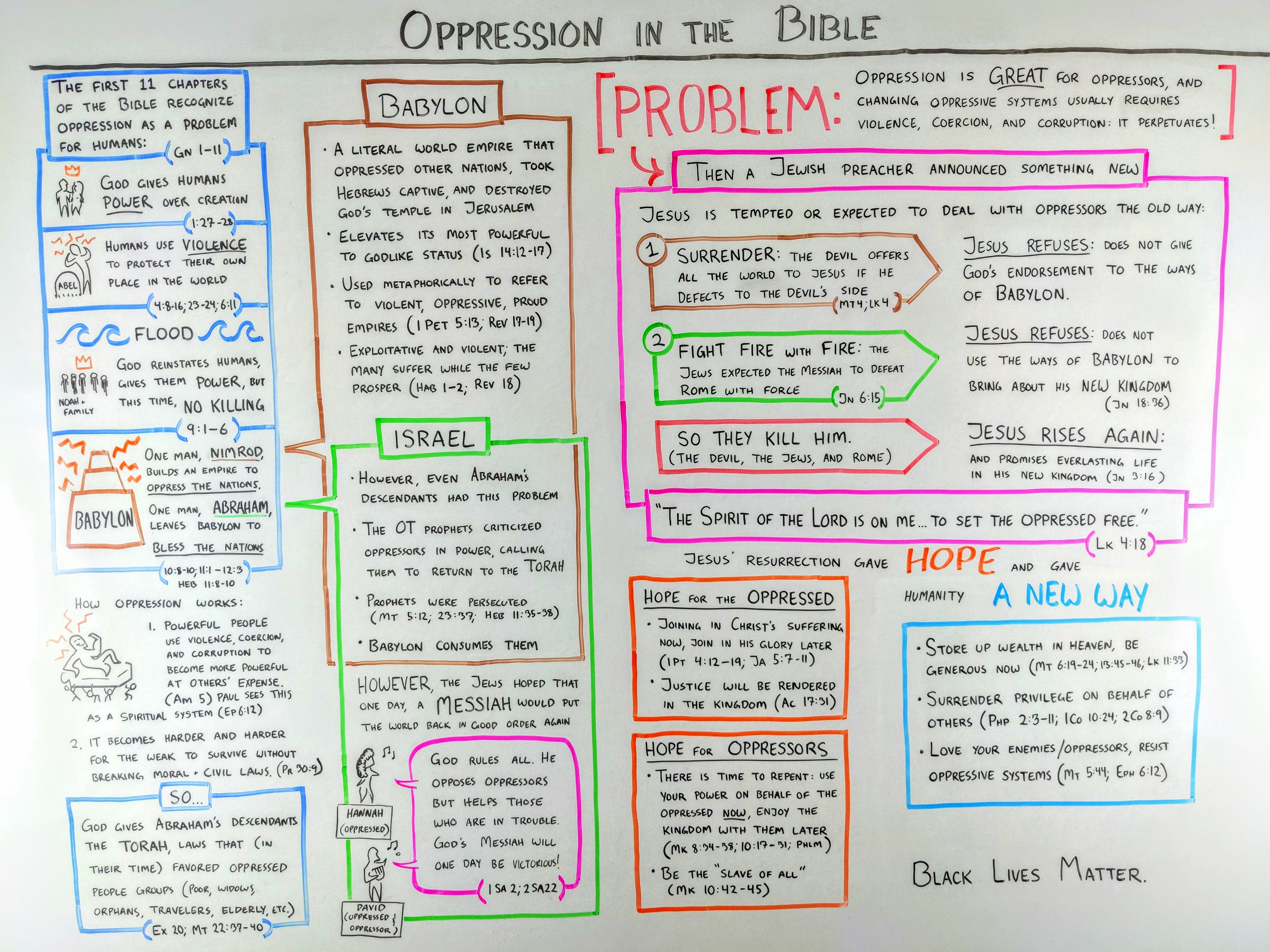

If you want to understand the Bible (and if you want to understand the world), you need to understand the problem of oppression. It’s one of the key problems that the writers of Scripture address from the first book of the Bible to the last.

In this guide, we’re going to get an overview of how the Bible deals with the problem of oppression. Here’s what we’re going to cover:

No matter what you believe about the Bible and the Christian faith, you’ll likely find yourself in a conversation about oppression with someone who thinks the Bible is important. I wrote this to help you navigate these conversations.

Oppression: “My power at your expense”

Oppression is the unjust use of power at other people’s expense. It involves protecting one’s power, comfort, security, and privilege at the expense of those with less of these than you. It’s a tricky concept to address, because if you’ve ever experienced oppression, you probably don’t need it defined to you. If you need oppression defined, you’ve probably participated in it.

It’s easy to recognize oppression at the individual level. It’s the evil stepmother forcing a girl to do the housework. It’s the slithery manager harassing his assistant. It’s the schoolyard bully taking your lunch money. But oppression isn’t just a few thorns—oppression is a worldwide, overgrown briar patch that entangles us at the civilization level.

We observe oppression all around us, and on some level, we all know oppression is wrong. (At least, we know it’s wrong when we’re the ones being oppressed.) But undoing it is easier said than done.

This is not a new problem. Powerful people have oppressed the weak for millennia. But the authors of the Bible believed (and many people today believe) that oppression can be done away with, eventually.

The biblical origins of oppression

The Bible is a vast collection of ancient documents, called “books.” These books are divided into two main sections: the Old Testament, which deals with the relationship between the ancient Israelites and their God, and the New Testament, which was written by the first-century followers of Jesus Christ. We’re going to see the theme of oppression developed across both of these sections, but for now, we need to look at the first few chapters of the first book of the Old Testament: Genesis.

The first eleven chapters of Genesis form a prologue for the rest of the Bible. These stories set the stage for how the ancient Jews viewed the world: the spiritual and the physical realms. In the beginning, God creates the world, forging order and safety out of chaos. God then gives humanity the power to rule over and care for the world (Gn 1:27–28; 2:15).

It starts with a murder

However, the next generation of humans begins using their power against each other. Cain is jealous of his brother Abel, and kills him. While Cain is a human tasked with ruling over creation, he doesn’t believe that it’s his responsibility to look out for his brother.

Then the LORD said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?”

“I don’t know,” he replied. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Gn 4:9, emphasis added)

And so people begin to use violence and coercion to get their own way. But this puts people at odds with the good order of the world (Gn 4:11–12), and the cycle of violence quickly escalates. A few generations later, one of Cain’s descendants, Lamech, brags to his wives about how he’s become strong enough to murder anyone who so much as hurts him (Gn 4:23). This violence crescendos until the author(s) of Genesis conclude(s) that all of humanity’s thoughts were thoroughly, constantly evil (Gn 6:5).

Everyone, that is, except one person named Noah.

Humanity’s second chance

The ancient Hebrews believed that God sent a flood to wash away this violent civilization, but he gave Noah, his family, and a few animals a second chance. (They famously survive the waters in an ark.)

Once again, God blesses humanity with power and authority over the world. But this time, God adds a caveat: don’t kill each other. God warns that if you shed someone’s blood, then someone else is going to come for you. The cycle of violence just ended in the flood—and God warns the people of earth not to restart that cycle (Gn 9:1–6).

They don’t last long, though. Within a few generations, a violent warrior-king named Nimrod begins building an empire, which includes the tower of Babylon (Gn 10:8–12; 11:1–9). If you were hearing this story for the first time as a first-century Jew, your ears would perk here. Later in the Bible, Babylon will become the icon of oppression in the world. And this is where the prologue ends: with violence and coercion as part of the human condition, and with humanity on track to build cruel, oppressive empires.

How oppression works

Oppression works in the Bible the same way it works today: the powerful take more for themselves at the expense of the weak. This is done in several ways:

- Violence. Being physically strong on an individual level or militarily strong on a larger scale allows some people to simply take what they want. It’s the crudest form of oppression, and the earliest that we see in the story of Scripture. (Examples include Cain, Joseph’s brothers, and Pharaoh.)

- Coercion. Sometimes violence isn’t necessary—the threat of violence, or the threat of negative consequences for not appeasing the powerful is enough to keep the weak in line. Pharaoh does this when keeping the children of Israel enslaved by upping their work quotas.

- Corruption. If you’re powerful enough, you can influence or create systems to keep you in power automatically. A common way this was expressed in ancient times was through bribes. Judges had the power to pronounce rulings in courts. But rich, powerful, high-status families could bribe judges to rule in their favor.

- Veneration. And if you’re really powerful, you can get people to treat you like a god. By positioning yourself as the source of everyone else’s power, security, and status, you get to define what’s right and wrong in the domain under your control. This means your followers will do the work of oppressing those who oppose you, and even the people you’re oppressing might love you.

This affects the weak in obvious ways. They’re subject to fraud, abuse, slavery, rape, homelessness, and death—and that’s if they stay on the “right” side of the law. If an oppressed person should find themselves on the “wrong” side of the law, they’re helpless against the system. A poor person has to choose between survival and breaking the law, or their own moral conscience—a struggle the oppressors never have to face.

For example, in the book of Proverbs, a sage says he doesn’t want to become rich—as this would lead to him denying the Lord. But he also doesn’t want to become poor and have to choose between starvation and stealing (Proverbs 30:8–9). To some readers, this might seem like an obvious “do the right thing” scenario. If you’re poor, you can still choose to do what’s right and not steal—and if you steal, you face the consequences.

But this is key to understanding how the authors of the Bible viewed this problem: in an oppressive system, the powerful people are already stealing from the weak; they’re just not prosecuted. The prophet Ezekiel says this about the wealthy families, the government authorities, and the religious leaders in Jerusalem during his day:

The people of the land practice extortion and commit robbery; they oppress the poor and needy and mistreat the foreigner, denying them justice. (Ezekiel 22:29)

You can see how this is a problem. Oppressive systems create a double standard, allowing the powerful to get away with things the weak would never be able to do. This isn’t just an issue with primitive civilizations. People are still protesting systemic injustice today. For example, in the USA, a black man accused of paying with a counterfeit $20 bill can lose his life, while a white man accused of ethnic cleansing and war crimes can get his face on the $20 bill.

Oppression is a flywheel that keeps on turning

Oppressive systems self-perpetuate: the powerful grow more powerful, which makes it easier for them to take even more from the weak. Physically stronger men can oppress physically weaker women. Wealthier classes can oppress classes of lower status. Societies with more advanced technology can oppress weaker, poorer societies. There’s always someone else to oppress.

Reversing oppression is difficult, because in an oppressive system, there’s not much reason for the powerful people to change things. Why would someone give up their position of power? Wouldn’t that just leave a power vacuum for someone else—someone less trustworthy than yourself—to swoop in? The author of Ecclesiastes explores this problem: the more powerful you become in an oppressive system, the more invested you become in maintaining that system:

If you see the poor oppressed in a district, and justice and rights denied, do not be surprised at such things; for one official is eyed by a higher one, and over them both are others higher still.

[…]

Whoever loves money never has enough;

Whoever loves wealth is never satisfied with their income.

This too is meaningless. (Ecclesiastes 5:8, 10)

Dismantling an oppressive system from the inside requires the ones who benefit most to sacrifice their power and comfort. That’s not easily done.

And beyond this, most oppressors don’t think of themselves as oppressors. In fact, oppression can often feel like doing the right thing—or at least doing the necessary thing. The “us vs. them” mentality runs deep in humanity, and so it’s easy to justify prejudice and corruption with arguments like:

- “It was either them or me.”

- “I’m doing what I have to do to protect my family.”

- “If I look weak, I’m inviting people to take advantage of me.”

- “Life’s not fair.”

- “If they want a different outcome, they should have made better decisions.”

- “I can’t become complacent and settle for less.”

It’s difficult for an oppressor to have any qualms with their way of life. And it’s almost impossible for an oppressed person to convince an oppressor that they’re doing anything wrong.

So if the oppressors won’t listen to the oppressed, the underdogs will eventually overthrow their overlords and be free, right? Unfortunately, while power changes hands from person to person and empire to empire, the oppression doesn’t go away. When an oppressive person, or group, or society declines, they’re usually replaced by yet another oppressive force.

The writers of the Bible associated this problem of oppressive world systems with one empire in particular: Babylon.

Babylon: the icon of oppression in the Bible

We first encounter Babylon at the end of the Bible’s prologue, in chapters 10 and 11 of Genesis. You’ve heard the story of the Tower of Babel—the Hebrew word translated “Babel” in Genesis 11 is the same word that’s translated “Babylon” through the rest of the Old Testament. This is an empire that eventually goes on to consume the Ancient Near East, including famously sacking the city of Jerusalem and razing the temple of God (2 Kings 25).

There were other oppressive kingdoms in the world, of course. According to the Torah, the ancient Israelites were enslaved in Egypt for 400 years (Gn 15:13; Exodus 12:40). During the time of the Judges, the Israelites were oppressed by several surrounding nations. But no nation quite distinguishes itself in the biblical narrative like Babylon.

That’s because while Babylon was a literal world empire, the authors of Scripture saw it as something more than flesh-and-blood. Babylon represents what happens when humans acquire enough power to elevate themselves to godlike status. It begins with humans attempting to build a tower to heaven, asserting themselves in the face of God and the other spiritual beings of their time (Gn 11:4).

Later, the prophet Isaiah describes the king of Babylon as someone who, like the builders of the tower of Babel, aspires to godhood (Isaiah 14:12–14).

And just before they sack Jerusalem, the prophet Habakkuk describes the Babylonians as a people who worship their own military strength:

“Guilty people, whose own strength is their god.”

—God (Habakkuk 1:11)

The Hebrews believed Babylon’s hunger for oppression disrupted the good, intended order of God’s world. Habakkuk says that humanity was originally supposed to be like the fish of the sea—they don’t need to be dominated by rulers in order to enjoy the ocean. God originally set up humanity as caretakers, not conquerors. But Babylon’s taste for conquest and domination is like a fisherman with a net: they plunder the nations of the world and consume them (Hab 1:14–16).

The literal empire of Babylon doesn’t last forever. Eventually the Persian king Cyrus the Great overthrows Babylon and allows the people of Israel (and other nations) to return to their homelands and practice their own religions. But while the Babylonians aren’t in charge, the spirit of Babylon is far from dead. The first century followers of Jesus use the word “Babylon” to symbolically refer to oppressive, exploitative systems—Peter refers to Rome as Babylon (1 Peter 5:13), and John writes down a vision of a mysterious woman named Babylon who has entranced all the kingdoms of the world (Revelation 17–19).

Babylon is the first oppressive empire, and represents humanity’s tendency to elevate themselves to godlike status by oppressing and dominating the world around them. However, the writers of Scripture believed that shortly after humans founded the empire of Babylon, God began sowing the seeds of a different sort of kingdom.

Israel: a holy nation?

Just as the Bible’s prologue closes, God calls Abraham to leave the land of the Babylonians and start something new. While Babylon is seeking to oppress the nations, God wants to use Abraham to bless the nations (Gn 12:1–3). Abraham’s descendants become the nation of Israel, a people group that God rescues from their oppressors in Egypt and makes his own special nation.

The ancient Israelites believed that before Israel migrated to the promised land, God gave them a set of instructions to follow in order to stay in the land God was giving them. These instructions were known as the Torah, the laws given to Israel in the first five books of the Bible. The people of Israel believed that the Torah set them apart from the other nations in their area of the world. Some of these laws are still famous today, such as abstaining from shellfish and not working on the seventh day of the week.

However, much of the Torah is written to make it more difficult for oppressive systems to take root in Israel as they thrive in their land. At the end of the Torah, the great prophet Moses gives Israel a set of laws that would guide them to live in harmony with God and the land. On multiple occasions, Moses warns that Israelites who oppress traditionally downtrodden people groups are not in harmony with their God:

For the LORD your God […] shows no partiality and accepts no bribes. He defends the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and loves the foreigner residing among you, giving them food and clothing. And you are to love those who are foreigners, for you yourselves were foreigners in Egypt. (Deuteronomy 10:17–19)

Cursed is anyone who leads the blind astray on the road. (Dt 27:18)

Cursed is anyone who withholds justice from the foreigner, the fatherless or the widow. (Dt 27:19)

Cursed is anyone who accepts a bribe to kill an innocent person. (Dt 27:25)

[Emphases added, obviously.]

The authors and editors of the Torah believed living in harmony with God and the land involved seeking justice for widows, orphans, immigrants, the disabled, and the poor. These people would otherwise fall victim to oppressive systems, so the Torah sought to build corrective checks against oppression. When farmers harvested their crops, they were to leave behind anything that they missed on the first pass for the poor to glean (Dt 24:17–22). Financial debts were to be canceled every seven years (Dt 15:1–11). All Hebrew slaves were to be freed after six years of service, and liberally furnished with what they needed to start a new life on their own (Dt 15:12–15). Land was to be returned to its original families every fifty years (Leviticus 25:10). The Torah came with these built-in resets that, if observed, would counteract the oppressive tendencies of human society.

NOTE: If you’re very familiar with the Torah, then you know that there are portions of the Torah that we’d consider unacceptable and oppressive today—things like genocide and enslavement. There’s a lot to unpack there. But for now, suffice it to say that as far as the ancient Israelites were concerned, they were holding themselves to a higher standard than the nations around them. But over time, barbaric practices were seen as less compatible with God’s character. For example, the book of Deuteronomy says that God wants Israel to wipe out the inhabitants of the promised land—so that they don’t intermarry and tempt Israel to worship other gods (Dt 7:1–6) . But the later work of Jonah (satirically) laments that God’s character prefers to lavish love and compassion on non-Israelite people, rather than destroy them (Jonah 3:10–4:2).

Israel oppresses her own

Unfortunately, the nation of Israel becomes oppressive itself. Israel’s priests and religious leaders become corrupt, defrauding the poor, accepting bribes, and taking advantage of women (1 Samuel 2:12–17; 22; 8:1–4) and so the nation opts for a monarchy. However, their first king, Saul, commits genocide against second-class citizens (2 Samuel 21:2). Their second king, David, does better, but still abuses his power and orchestrates his own friend’s death in order to take his wife (2 Sa 11). David’s son Solomon enslaves many non-Israelites. And Solomon‘s son Rehoboam’s threats of further oppression lead to the kingdom splitting in two (1 Kings 12).

Things only get worse from here on out. Most of the leaders of both kingdoms fail to observe the Torah—escalating to the point of one particularly wicked king “filling Jerusalem with innocent blood” (2 Kings 24:3–4). The rich bribe court officials, and the courts accept the bribes (Amos 5:12–13).

This didn’t go completely unchecked. At various points in Israel’s history, people would stand up and challenge the oppressors. They echoed Moses’ warnings of how oppressive systems would end up ejecting everyone from the land, and called the people to turn away from their oppressive ways. These people are known as the prophets. The prophets warned the people of coming judgment, but also anticipated a future in which God himself would establish a kingdom on earth—and finally Israel and the whole world would have justice and peace.

Though their words have been preserved for millennia, most of these prophets were persecuted or martyred for the messages (Matthew 5:12; 25:37; Hebrews 11:35–38).

The Old Testament tells the story of the prophets calling the leaders of Israel to abandon their oppressive systems time and time again—but the people didn’t change. So eventually the land expels them, and the descendants of Abraham are overcome by the world empires they were supposed to counteract. The rebel kingdom falls first to Assyria. The kingdom ruled by David’s line in Jerusalem is consumed by Babylon itself.

The hope of Messiah

However, the writers of the Old Testament thought there was hope that one day, a leader in Israel would break this cycle of oppression. The books of 1 & 2 Samuel tell the story of Israel’s rise from a confederation of tribes to a united kingdom, and that story is framed by two poems—one at the beginning, and one at the end (1 Sa 2; 2 Sa 22).

The former is spoken by an oppressed woman named Hannah. The latter is written by David, a king who knew what it was like to be both oppressor and oppressed. Both of these poems state that God is the ultimate authority, who opposes prideful oppressors but helps the weak. Both Hannah and David anticipate a time when the Messiah, a ruler in Israel anointed by God, would put things to right, and claim victory over the oppressors.

If you’re familiar with the Bible, you know that Christians believe this Messiah figure has already started doing this.

Jesus vs. Oppression

Time goes by, and the world changes hands. By the first century, the Jews live scattered across the world, and their homeland is under the oppressive rule of the Roman empire.

During this time, a man named Jesus arrives on the scene. After being baptized by another popular teacher (John the Baptist), Jesus goes into the wilderness, where he is tempted by the devil.

The devil is an interesting figure in the Bible—because by the time of Jesus, the first-century Jews saw him as the one at the top of Babylon’s pyramid scheme (John 12:31; Ephesians 2:1–2; 1 John 5:19). This spiritual figure had somehow made the systems of the world his own, so much so that he can offer Jesus all the kingdoms of the world. The only catch? Jesus needs to worship the devil—conceding that the devil’s means of ruling the people of earth was acceptable. Jesus refuses this offer (Mt 4:8–11).

From this point onward, Jesus begins proclaiming the coming of a new kingdom: the kingdom of heaven or the kingdom of God. This is exciting news to some of the Jews. A prophet had come from David’s line—someone they assumed would violently overthrow their oppressors in Rome and restore Israel to her former glory. On at least one occasion, a faction of the Jews begin a movement to make Jesus king by force (Jn 6:15).

However, the authors of the New Testament believed Jesus was taking a different approach to establishing a kingdom. Jesus says that his kingdom is not of this world, and so his followers don’t need violence to overthrow oppressors (Jn 18:36). Jesus stops his followers from fighting back when he is arrested—and even heals the one person whom his followers injure (Luke 22:49–51). Jesus knows that he’s about to die, but he reminds his followers of the cycle of violence that God warned Noah about all the way back in the prologue of the Bible (Gn 9:6):

Put your sword back in its place,” Jesus said to [Peter], “for all who draw the sword will die by the sword.” (Mt 26:52, emphasis added)

The world, on the other hand, has no problem using violence and corruption to put Jesus to death. Jesus, an innocent man, is arrested, tried, tortured, and killed as a criminal.

However, death doesn’t take. Jesus’ followers claim that he rose from the grave on the third day—demonstrating that the old, oppressive way of the world was powerless over him. Jesus wasn’t going to come in and assert his authority the same way every oppressor had since Cain killed Abel. Instead, Jesus bore the full blow of the oppressor: and rose again. Christians later said that this act of suffering and resurrection put the way of the world on display: their time has come to an end (Jn 12:31–32; 1 Jn 4:4).

Having disarmed the powers and authorities, [Jesus Christ] made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross. (Col 2:15)

The hope of resurrection

To the early Christians, and to many people today, Jesus’ resurrection brought hope that oppression could be undone. Jesus’ followers believed that eventually, the oppression of Babylon would collapse (Revelation 17–19) and Jesus Christ’s kingdom would be fully established on earth, as it is in heaven (Mt 6:10). A kingdom in which there would be “no more death or mourning or crying or pain,” because the “old order of things” will have finally passed away (Re 21:4).

For the early Christians, Jesus’ resurrection brought two important realizations to bear:

- This life isn’t all there is—there’s the possibility of being alive after you’ve died.

- If Jesus’ kingdom really works the way he said it does, then things will be very different.

The possibility of another life in an oppression-free world gave hope to the oppressed. But it was a warning to the rest.

Hope for the oppressed

The oppressed people had the hope that while this life may be full of suffering, there was something better ahead. The early Christians believed that just as Christ suffered on behalf of those he came to rule, they too could suffer. They believed that Christ invited them to join in his sufferings, and those who could suffer oppression while still showing love to their fellow humans would eventually join Christ in the glories of the world to come (1 Peter 4:12–19).

The early Christians believed that the wrongs that had been done to the oppressed would be put to right, and that justice would one day be truly reckoned. The Christians believed that Jesus would one day judge the world—not in a judgmental, negative way, but as a fair, compassionate king. They believed that everyone, whether living or dead, would finally be dealt with fairly (Acts 17:31).

The oppressed were told to be patient, and to eagerly await that day (James 5:7–11).

But in the meantime, the followers of Jesus were to provide a place of sanctuary from the world to the oppressed. This is why the first-century Christians devoted so much time and resources to caring for poor and downtrodden people in their midst. Wealthy Christians sold their property and distributed the wealth to those who needed it (Ac 4:32–35). Even Christians who were less well-to-do gave sacrificially to help those with even less (2 Corinthians 9:2–4). Jesus taught that his followers would be recognized by how they treated the poor, the imprisoned, and the “least of these” people—it was expected that his followers create oppression-free zones around the world, setting the world free from oppression one act of kindness at a time (Mt 25:31–40).

Hope (and warning) for the oppressors

But what about the people who played into the systems of oppression? What about the wealthy? What about the violent? What about the corrupt?

The early Christians believed that there was hope for the oppressors, too—but it came at a price. Jesus expected privileged people to divest themselves of their power on behalf of those without it. It’s the opposite of how the world works, but Jesus made the offer: anyone who is willing to abandon the oppressive systems of this world in order to build the systems of the kingdom would not go unrewarded (Mk 8:34–38; 10:17–31).

You can probably see why Jesus said it would be easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich, powerful person in this world to succeed in his kingdom (Mt 19:23–30). It takes great faith to walk away from power and privilege now on the off-chance that you’ll find greater rewards in the next life. Jesus promised that in order to be great in his kingdom, you had to be the slave of everyone here and now (Mk 10:42–45).

That’s a bitter pill to swallow for people (like me) who benefit from oppressive systems.

The oppressed were told to be patient—the oppressors were told to forfeit what they had.

Both the oppressed and the oppressors were given a new way to live. A way to undo oppression here and now, in anticipation of Jesus’ return.

A new way

First-century Christians (and many people today) believe that there’s a new, better way to live. Unlike Cain, unlike Babylon, and unlike Israel, people can subvert the norms of violence, coercion, and corruption, and start bringing about the new world now.

The early Christians believed in a different approach to wealth. Jesus taught his followers to be generous with resources on earth, and instead to store up treasures in heaven: rewards a hundred times better than anything given up here and now:

“Sell your possessions and give to the poor. Provide purses for yourselves that will not wear out, a treasure in heaven that will never fail, where no thief comes near and no moth destroys. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” (Lk 12:33–34)

Likewise, Christians had a self-sacrificial view of privilege. The apostle Paul urged Christians to set aside their own interests in favor of the interests of others (Philippians 2:3–11; 1 Corinthians 10:24). Paul believed that Jesus Christ had set the example for his followers: he sacrificed himself, knowing that the reward for doing so was far greater than the price paid.

For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich. (2 Corinthians 8:9)

But what about the people who oppressed the Christians? The followers of Jesus believed that the best response was to love the oppressors, yet resist the oppressive systems. Jesus encouraged his followers to love their enemies and pray for those who persecuted them (Mt 5:44). And the apostle Paul reminded his readers that their struggle was not against flesh and blood, but against the evil systems of the world (Ep 6:12).

That’s an important thing to keep in mind, because oppression is just as big a problem today as it has been for millennia. For example, as I write this guide, US citizens are protesting the murders of innocent black people at the hands of law enforcement, and systemic issues that negatively impact people of color here.

What can we do to end oppression?

Oppression is how the world works, which is why it takes faith to undo it. The early Christians, and many people today, believe that it won’t always be that way. But the end of oppression isn’t just a pie-in-the-sky future: it’s something that the early church believed Christians were tasked with bringing about in the meantime.

Before Jesus died at the hands of his oppressors, he prayed for his followers who would come after him. Jesus saw his followers as being in the world, but not of the world (Jn 17:16). The moment someone becomes a follower of Jesus, their allegiance is to him, and they’re bound to follow the ways of his kingdom, not the oppressive ways of the world. This involves patiently enduring suffering and cheerfully sacrificing privilege, power, and wealth on behalf of those who need it (2 Co 9:7).

Jesus warned that his kingdom comes at a cost, which makes sense. Jesus was killed by the oppressive systems of the world, and he tells his followers to expect the same to happen to them:

Remember what I told you: ‘A servant is not greater than his master.’ If they persecuted me, they will persecute you also. (Jn 15:20)

The followers of Jesus eagerly await a day when the world will be put to right and “in His name, all oppression shall cease.” But in the meantime, the New Testament instructs followers of Christ to live in faith as though the kingdom has already come—creating pockets of an oppression-free world here and now.