If you’re not paying close attention, it’s easy to get confused about the Herods in the New Testament. I’d been a Christian for quite a while before realizing that my understanding of Herod was off. It finally hit me one day that the same Herod probably wasn’t at Jesus’ birth and still tormenting the disciples 50 years later. Suddenly, the light came on, and I asked myself, “Is there more than one Herod?”

I know. I can be a little slow on the uptake. But to be fair, it’s pretty confusing. Sometimes the gospels present the various Herods (the Great, Antipas, Agrippa I, etc.) simply as “Herod.” If you’re not aware of the Herodian dynasty, you’re probably not going to catch some of the gospels’ political intrigue.

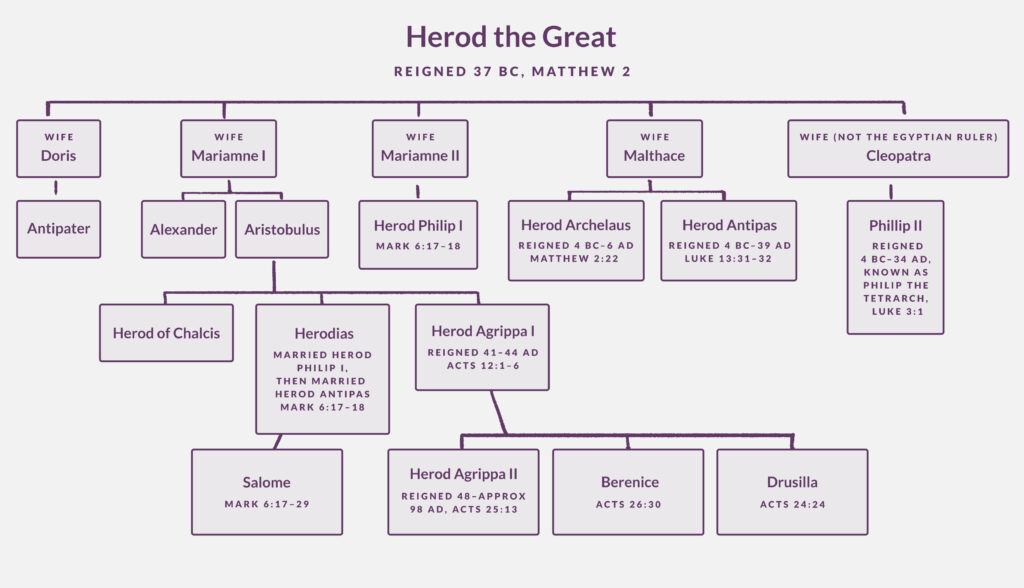

The Herod family tree is quite large. (And it’s incredibly interesting.) The cast for this diabolical sitcom includes (but is not limited to) the following biblical characters:

Let’s dive into this fascinating family and see how getting to know them a little better impacts our grasp of Jesus’ story.

Where it all began

The Herodian dynasty really begins with Herod the Great’s father, Antipater. Antipater was an Edomite. If you’re not familiar with Edom, a little background is going to be helpful here.

Who are the Edomites?

Edomites were thought to be the descendants of Esau, the elder brother of Jacob (the Israelite patriarch). In fact, Israel often calls their nation Edom’s brother (Num. 20:4, Deut. 2:4–5, Amos 1:11, Obad. 1:10). And just like the troubled relationship between the two brothers, Israel and Edom never really got along.

It seems that Edom was complicit with Babylon’s conquest of Israel. The prophet Obadiah explained it this way:

“On the day that you stood aloof, On the day that strangers carried off his wealth, And foreigners entered his gate And cast lots for Jerusalem—You too were as one of them” (Obadiah 1:11).

Like a kid who received beatings and wedgies from classmates every day while his brother looked on, Israel never got over the fact that Edom allowed their enemies to ransack them. The Israelites excelled at holding grudges (Amalek, anyone?), so an understanding of Herod’s bloodline will help illuminate the relationship between Herod’s family and Israel.

And even though Josephus tells us that Antipater’s family had embraced Judaism, they would always be viewed with skepticism among the Jews.

Antipater’s rise to power

Herod’s father had married into some wealth and nobility. Antipater rose in the ranks of the Hasmonean dynasty and became an influential adviser. And while there’s a lot of intrigue in Antipater’s story, we’ll just hit the high points so we can get on with the Herods.

- He backed Pompey’s conquering of Israel in 63 BC.

- He allied his family with Rome.

- Julias Caesar made Antipater a Roman citizen and the procurator (civil and judicial administrator) of Judea.

- He made his 26-year-old son, Herod, governor of Galilee.

- He was murdered by Malichus I in 43 BC.

Herod the Great

After the death of his father Antipater, Herod the Great (still governor of Galilee) established a close relationship with Mark Antony—one of the renowned ringleaders of Julius Caesar’s assassination. Because he trusted Herod, Antony set things in motion to install Herod in Judea in place of its current ruler, Antigonus.

When civil war broke out between Octavian (also known as Augustus Caesar) and Mark Antony (allied with his wife Cleopatra of Egypt), Herod found himself aligned with the losing side. After Mark Antony’s suicide, Herod threw himself on Octavian’s mercy, admitting that he had backed Antony’s party against him and promising his allegiance.

Always the pragmatist, Octavian saw in Herod the ruler he wanted in Palestine. The Roman senate nominated him the king of Judea and equipped him with his own army. So in 37 BC, at the age of 36, Herod became King of the Jews—a position he’d hold for about 37 years.

Herod rebuilds the temple

The king of Judea was in an awkward position of having to please his Jewish subjects and his Roman superiors. On top of that, Herod wanted desperately to present himself as a cultured and erudite figure. Instead of focusing on the affairs of Israel, Herod would often entertain Roman dignitaries, poets, and philosophers.

Between Roman rule and Greek culture, the Jews were looked down on as an influential, but primitive group. And Herod was basically a king of the nerds desperate to ingratiate himself with the jocks and homecoming queens. This is why he made decisions that only hurt his relationship with the people he ruled.

For instance, he built the port of Caesarea Palaestinae on the coast between Joppa and Haifa. It was no small feat of engineering. It featured an artificial harbor protected by concrete breakwaters. It sported pagan temples dedicated to Roma (the goddess who personified Rome) and Caesar Augustus himself. Every fifth year, Herod staged gladiatorial fights to honor the emperor and his wife.

Herod’s opulence was only kept in check by his need to maintain a relationship with Jewish leaders. But his pagan temples didn’t do him any favors. The Pharisees and High Priests held Herod in contempt, and even when Herod carried out his duties as a leader of Israel, they were suspicious of his motives. It didn’t help that he had earlier established a reputation for cruelty as the governor of Galilee.

Herod’s big plan to curry favor with the Jews involved a magnificent temple upgrade. After the Persians conquered Babylon in 538 BC, Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to rebuild their temple. While the new temple maintained the same dimensions as the original, it never matched Solomon‘s original splendor. On top of that, the temple had sustained some damage under the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV and again during Pompey’s siege of Jerusalem. Herod thought he could do better.

With an army of carpenters numbering in the thousands, he began work on the temple. Levites had to be trained as stonemasons to work on the temple’s more sacred areas. Most of the construction was completed in 10 years, although some of the finish work and decoration wouldn’t be completed until about 64 AD (just in time to be destroyed again six years later in the First Jewish–Roman War).

It would be difficult to overstate how the temple turned out. Very few building projects were as ambitious. Not only did Herod want to please the Jews, but he wanted a legacy. When Jews gathered for worship (or even saw the temple glittering on the horizon), he wanted them to think of him. But over time, even the temple became a source of stress.

Herod’s dysfunctional family

As we’ll soon see, Herod wasn’t the most stable character in Israel. He was married 10 times. Of those ten wives, historians know the names of eight: Doris, Mariamme I, Mariamme II, Malthace, Cleopatra (no relation to the Egyptian ruler), Elips, Pallas, and Phaidra. We’re going to zero in on the ones who intersect with the biblical story.

Doris

Herod married his first wife—Doris—in 47 BC while he was still the governor of Galilee. The historian Josephus tells us that her family was from Jerusalem. She bore him his first son, Antipater (named for Herod’s father).

When Herod showed up in Judea to oust Antigonus and take the throne, he ended up marrying Antigonus’ niece Mariamne. This (like most of Herod’s marriages) was a purely political move to give some legitimacy to his ascension.

Of course, the existence of Doris and Antipater made this new marriage a problem. So Herod banished her and his son. Many years later, Antipater and his mother were welcomed back into the court. But as Herod was nearing death in 4 BC, there was some intrigue in which Doris and Antipater were implicated. Herod had his son executed, and Doris was banished . . . again.

Mariamne I

Herod’s second marriage was one of political convenience. Since he had put most of her family to death, Mariamne wasn’t a massive fan of her new husband. Mariamne was known to speak back to her husband in ways that others were afraid to. Her contentious relationship extended to Herod’s mother and his sister, Salome. The tension around the palace was so terrible that Salome and her mother made up a story that Mariamne was in love with Mark Antony and that she sent her portrait to him in Egypt.

While the Roman civil war was raging, Herod visited Antony in Egypt, putting Salome’s husband, Joseph, in charge of Mariamne. Because of the tensions with the war, Herod nursed some fear that Antony would put him to death. He put Joseph under strict orders to kill Mariamne if Antony had him executed.

It turns out that Joseph was a dummy. In an effort to convince Mariamne of Herod’s love for her, he told her about Herod’s order (because nothing says true love like “if I die, please kill my wife”). The historian, Josephus, tells us that when Herod found out that Joseph opened his big mouth, he had them both killed.

Mariamne bore Herod three sons. One tragically died in his youth. The other two (Alexander and Aristobulus) would be put to death toward the end of Herod’s life.

Mariamne II

After the death of his second wife, Herod met another Mariamne. By all reports, she was gorgeous, and Herod fell in love with her. Her father, Simon, was a nobleman from priestly descent, so Herod appointed him to the high priesthood and took his daughter as his wife.

Mariamne II bore Herod another son, Herod Philip I. Herod Philip would have succeeded Doris’ son, Antipater to the throne. So when Mariamne found out that Antipater intended to kill his father, she kept his secret. When Herod discovered Mariamne’s knowledge of the plot, he sent her away, and Herod Philip was never allowed to reign.

Herod Philip married his niece, Herodias. And the poor guy is embarrassingly memorialized in Scripture as the schlub Herodias left to marry his uncle (a different Herod):

For Herod himself had sent and had John arrested and bound in prison on account of Herodias, the wife of his brother Philip, because he had married her. For John had been saying to Herod, “It is not lawful for you to have your brother’s wife” (Mark 6:17–18).

Malthace

We don’t know a lot about Malthace. We do know she was a Samaritan woman (the Jews must have loved this). She gave birth to Herod Archelaus and Herod Antipas.

Cleopatra of Jerusalem

Obviously, we call this wife Cleopatra of Jerusalem to ensure that no one confuses her with her more famous namesake. She and Herod gave birth to Philip the Tetrarch.

Herod’s family loses their everloving minds

As you’ve probably started to piece together, Herod the Great lacked some interpersonal skills. As a matter of fact, as his rule went on, he kept leveling up in crazy. Herod’s court was full of drama and infighting, and this definitely didn’t help.

Mariamne I’s sons, Aristobulus and Alexander, were educated in Rome, often living with Augustus. When Antipater (Herod’s first son) was brought back into the kingdom, the wheels started to come off. Antipater was jealous of Herod’s favorite sons, and somehow talked Herod’s brother and sister into convincing the king that they were plotting to kill him.

Herod made Antipater his heir, but that wasn’t good enough. As long as they still lived, Herod’s firstborn saw them as a threat. So he continued to spread rumors about them. It got so bad that Herod took the issue to Augustus, charging Alexander and Aristobulus with treason. Augustus talked him out of putting his sons on trial and helped draft a plan for reconciliation.

Needless to say, that wasn’t going to work for Antipater, so the gossiping continued. Herod finally got Augustus’ permission to try his sons, and they were put to death. Now Antipater’s succession was set. Did that make him happy?

No. The idiot was impatient and made plans to poison his father. Herod found out, and Antipater was executed just days before Herod died.

Herod’s growing insanity

Throughout his life, Herod showed flashes of insanity. After having Mariamne killed, he would sometimes send servants to fetch her. As he got older and he grew more paranoid, things got worse. A lot of this came from the stress of trying to appease Rome and Israel and never truly succeeding at either.

When he tried to appease Rome by hanging a golden eagle (the symbol of Rome) at the temple entrance, he set off a firestorm. Young priests and devout Jews were incensed at the sacrilege. When rumors started circulating that Herod was melancholy and dying, a bunch of Jewish students saw this as a perfect opportunity to destroy the emblem. These rabbinical students chopped it down and destroyed it with axes, but soldiers caught about 40 of the rebels. Herod had them burned alive—along with their two rabbis.

Understanding his lack of popularity and worried that he wouldn’t be mourned in his death, Herod made plans for a mass assassination. He summoned notable individuals from all over Judea and had them imprisoned at the hippodrome theater in Jericho. When important figures from all over Israel died alongside Herod, he would assure mass mourning.

The order was given but it never carried out. It’s said that Herod’s sister, Salome I, released the prisoners and shared the details of the plot.

The birth of Jesus

In the midst of this madness, Jesus was born. While you might assume 1 AD was the year Jesus was born, scholars put Jesus’ birth between 6 BC–4 BC. The reason? Because we know that Herod the Great died around 4 BC, and his story intersects with the infant Jesus.

Knowing a little about Herod’s mindset at the end of his life helps us understand his response to the Magi. He’s been fighting tooth and nail to hold his dynasty together and consolidate his power. For Herod, the Messiah represents a complete and total loss of focus and power. Every ugly thing he’d had to do to maintain his position would have been a waste.

Initially, he planned to use information from the Magi to strategically remove Jesus. But when the Magi are warned in a dream not to return to Herod, he flies into a rage. It’s in this madness that Herod goes with plan B: kill every male child in Bethlehem two years old or younger (Matthew 2:1–18).

This is really the only time we hear about Herod the Great in the New Testament. In fact, Matthew immediately follows this story up with a nod to the regime change:

But when Herod died, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, saying, “Rise, take the child and his mother and go to the land of Israel, for those who sought the child’s life are dead.” And he rose and took the child and his mother and went to the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was reigning over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there, and being warned in a dream he withdrew to the district of Galilee (Matthew 2:19–22).

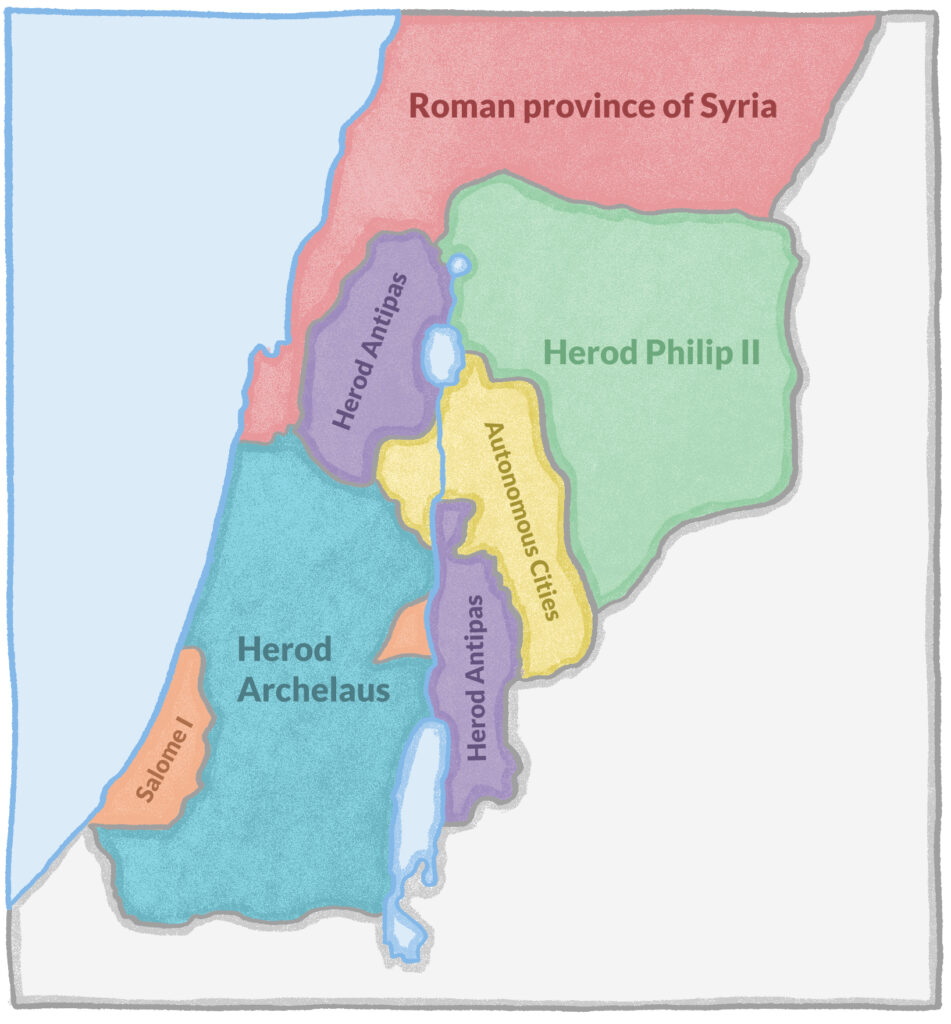

Because of his paranoia and ever-changing moods, Herod’s will was in constant fluctuation. Just before his death, he made one final change. This amendment made Archelaus the king of Judea, and the younger Antipas ruler over Galilee. But Herod didn’t have the power to make that decision unilaterally. It would require Augustus Caesar’s approval.

Of course, the whole production turned into a squabble between Herod’s sons, both of which thought they’d rule alone as their father did. Because Archelaus was known to be a bit of a monster, the senate was pulled toward making Antipas the sole ruler over the Jews. Augustus chose to honor Herod’s will, but refused to give Archelaus the title of king.

Herod and Cleopatra’s son Philip was made tetrarch (governor over one of four divisions) over the northern part of Herod’s kingdom. Herod’s sister, Solame I, was made queen over a small area, including Azotus, Iamnia, and Phasaelis.

Herod Archelaus

Not only was Archelaus part Edomite like this father, but he was also half Samaritan. You can probably imagine that this didn’t sit well with his Jewish subjects. But was Archelaus the type to patiently win over the Jews with wise and patient leadership?

Heck no. He may have been half Edomite, half Samarian, but he was 100% Herod. The Roman senate was right. He was a monster.

There was a lot of anger in Jerusalem after Herod the Great had those 40 students and two rabbis executed for destroying the Roman symbol. These wounds were still fresh when Archelaus took the throne. When rioting broke out at the temple during Passover, he sent in troops and 3,000 citizens ended up dying. The new king then canceled Passover.

When he left on a trip to Rome for his inauguration, rioting started again. It got so bad that even Archelaus’ troops couldn’t deal with the problem and the Roman governor of Syria had to step in with his legions. Over 2,000 people were crucified.

This chaos explains why Joseph was afraid to return to Judah, and instead went to Galilee where Philip was ruling.

Archelaus was such a terrible leader that both the Jews and Samaritans went to Rome to request his removal (and when you have the Jews and Samaritans working together, you know it’s a problem). He was deposed and sent to Gaul in 6 BC—he only ruled for two years.

Herod Antipas

Herod Antipas is the center of the gospels’ discussion about Herod. He’s the one John the Baptist called out for marrying his half-brother’s wife, Herodias. But if you want to get a firm handle on this relationship, it’s going to take a little work (so buckle up).

Sorting out Herodias

Herodias was the daughter of Aristobulus. You remember him, right? He was one of the two sons that Antipater badgered Herod into executing. Herod engaged Herodias to his other son Herod Philip I (the daughter of Mariamne II). This means that Herodias was initially married to her half-uncle—the one left out of the will because his mother didn’t alert Herod about Antipater’s murderous plot. (I know. It’s a bit confusing—and kind of icky.)

Philip and Herodias had a daughter named Salome (named after her great aunt). Like the rest of the Herodian dynasty, it appears that Herodias was a little too ambitious to be yoked to a Herod that was going nowhere, so she divorced him and married a different half-uncle, Herod Antipas.

Back to Antipas

When Antipas marries his half-brother’s wife, the Jews are less than enthusiastic. The gospel writers tell us that John the Baptist publicly called out Antipas for this sin. As a result, he had John thrown into prison (Luke 3:19–20).

It would seem that Herodias was cut from the same cloth as her grandfather. She couldn’t take the criticism and had it out for John the Baptist, but Antipas wasn’t interested in killing him. Mark tells us Antipas knew John was a holy man and enjoyed their challenging conversations (Mark 6:19–20).

But on Antipas’ birthday, everything went south. He threw a big gala, and all the high officials and military commanders were present. Herodias’ daughter, Salome, came in and danced for them. This went over so well that the (probably) drunk ruler made a public proclamation that he’d give Salome whatever she asked for (up to half of his kingdom). After consulting with Herodias, she asked for John the Baptist’s head.

Antipas was distressed, but he was in an awkward position and couldn’t refuse her.

Later, when the Pharisees are trying to get Jesus to leave the region, they tell him, “Leave this place and go somewhere else. Herod wants to kill you.”

Jesus responds, “Go and tell that fox, ‘Behold, I cast out demons and perform cures today and tomorrow, and the third day I reach My goal” (Luke 13:32). While we tend to use “fox” to describe a clever person today, first-century Jews would have understood a fox as an unclean animal that caused farmers’ problems.

Philip the Tetrarch

Philip largely avoided all the biblical drama since his area of rule didn’t include many Jewish settlements. He rebuilt the town of Bethsaida (the hometown of Peter, Andrew, and Philip), and later he would marry Salome, the dancing daughter of Herodias.

He’s only mentioned once in the Bible, “Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother Philip was tetrarch of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias was tetrarch of Abilene” (Luke 3:1, emphasis added).

Herod of Chalcis

The brother of Herodias and King Agrippa I, Herod of Chalcis ruled over the kingdom of Chalcis, which is in modern Lebanon. Eventually, Agrippa I asked Emporer Claudius to increase his brother’s kingdom. Herod of Chalcis was given the title of king over the territory north of Judea. When Agrippa died, he was given responsibility for Herod’s temple (along with the role of High Priest).

He is not mentioned in the New Testament.

Herod Agrippa I

Agrippa grew up around Rome. After Herod executed Aristobulus, Agrippa went to school with the son of emperor Tiberius. Agrippa’s extravagance put him in debt to the emperor. He was eventually offered a small post in Galilee by his uncle Antipas.

After paying off his loans, Agrippa was given a job tutoring Tiberius’ grandson, which is how Agrippa established a bond with a crackpot named Caligula. And it was also during this period that Agrippa made a wisecrack about the emperor that landed him in jail.

When Tiberius died and Caligula succeeded him, Agrippa was freed. Herod’s grandson was made king of the region ruled by Philip the Tetrarch. When his uncle, Antipas, attempted to turn Caligula against Agrippa, Caligula banished Antipas and gave his territory to Agrippa, too.

Unlike the rest of the Herod family, Agrippa ingratiated himself to the Jews by backing their persecution of the early church. In Acts, Luke lays out how Agrippa discovers the key to the Jews’ hearts:

Now about that time Herod the king laid hands on some who belonged to the church in order to mistreat them. And he had James the brother of John put to death with a sword. When he saw that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded to arrest Peter also (Acts 12:1–3, emphasis added).

It turns out that the whole “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” business works. Of course, when Peter got away, Agrippa had the guards killed because the nut doesn’t fall far from the Herodian tree (Acts 12:18–19).

The death of Agrippa I

Luke tells us that Agrippa’s Nebuchadnezzar-like hubris led to his death:

Now he was very angry with the people of Tyre and Sidon; and with one accord they came to him, and having won over Blastus the king’s chamberlain, they were asking for peace, because their country was fed by the king’s country. On an appointed day Herod, having put on his royal apparel, took his seat on the rostrum and began delivering an address to them. The people kept crying out, “The voice of a god and not of a man!” And immediately an angel of the Lord struck him because he did not give God the glory, and he was eaten by worms and died (Acts 12:20–23).

Sounds crazy, right? The historian Josephus documented it this way:

Now when Agrippa had reigned three years over all Judea, he came to the city Caesarea . . . There he exhibited shows in honor of the emperor. . . . On the second day of the festival, Herod put on a garment made wholly of silver, and of a truly wonderful contexture, and came into the theater early in the morning; at which time the silver of his garment was illuminated by the fresh reflection of the sun’s rays upon it. It shone out after a surprising manner, and was so resplendent as to spread a horror over those that looked intently upon him. At that moment, his flatterers cried out . . . that he was a god; and they added, ‘Be thou merciful to us; for although we have hitherto reverenced thee only as a man, yet shall we henceforth own thee as superior to mortal nature.’

Upon this the king did neither rebuke them, nor reject their impious flattery. But as he presently afterward looked up, he saw an owl sitting on a certain rope over his head, and immediately understood that this bird was the messenger of ill tidings, as it had once been the messenger of good tidings to him; and he fell into the deepest sorrow. A severe pain also arose in his belly, and began in a most violent manner. He therefore looked upon his friends, and said, ‘I, whom you call a god, am commanded presently to depart this life; while Providence thus reproves the lying words you just now said to me; and I, who was by you called immortal, am immediately to be hurried away by death. But I am bound to accept of what Providence allots, as it pleases God; for we have by no means lived ill, but in a splendid and happy manner.’

After he said this, his pain was become violent. Accordingly he was carried into the palace, and the rumor went abroad that he would certainly die in a little time. But the multitude presently sat in sackcloth, with their wives and children, after the law of their country, and besought God for the king’s recovery. All places were also full of mourning and lamentation. Now the king rested in a high chamber, and as he saw them below lying prostrate on the ground, he could not himself forbear weeping. And when he had been quite worn out by the pain in his belly for five days, he departed this life, being in the fifty-fourth year of his age, and in the seventh year of his reign.

What exactly did Agrippa die of? We can’t be sure, but it would seem that God demonstrated his displeasure in Agrippa in a most dramatic fashion. The best part of this story is the very next line from Acts: “But the word of the Lord continued to grow and to be multiplied” (Acts 12:24).

Herod Agrippa II

Agrippa II was about 17 when his dad died. He became a strong advocate for the Jews in Rome. He received authority over Jerusalem’s temple, and he also became king of Chalcis after the death of his uncle. When Phillip the Tetrarch died, Nero gave him authority over those territories, too.

Unlike his father, Agrippa II didn’t have much luck keeping the Jews on his side. And unlike his father, he didn’t exploit the Jewish hatred for Christians.

When Paul was arrested for stirring up trouble (and a bogus charge of attempting to desecrate the temple), he was brought before Antonius Felix—the Roman procurator of Judea. Like Agrippa I, Felix understood the political implications in dealing with Paul. When he realized that Paul wasn’t going to pay him a bribe, he held him for two years (to avoid upsetting the Jews).

When Porcius Festus replaced Felix in 59 AD, the chief priests and Jewish leaders began pressuring him to send Paul to Jerusalem for trial (their plan was to have him killed on the way there). Paul requested to have his case decided by Caesar, which was his right as a Roman citizen. But Festus had no idea what charges to send along to Caesar—so he consulted Agrippa II to get a better understanding of all the religious issues surrounding the Jews’ complaints.

So Agrippa and his sister, Berenice (or Bernice in the Greek New Testament) accompanied Festus to meet with Paul. As was Paul’s style, the apostle launched into a defense that was about 15 percent rebuttal and 85 percent apologetic discourse. At one point in his discussion about his conversion experience, Festus accused him of being insane.

After more exposition, Agrippa remarked, “In a short time you will persuade me to become a Christian.” Paul answered, “I would wish to God, that whether in a short or long time, not only you, but also all who hear me this day, might become such as I am, except for these chains” (Acts 26:28).

After their discussion, Agrippa and Festus decide that Paul has not done anything worthy of punishment. And Agrippa acknowledges that if it was up to him, Paul would be set free immediately—but because Paul had already appealed to Caesar, it was out of his hands (Acts 23–26).

In this moment, Agrippa demonstrated a real sensitivity to the situation without considering the political implications. Even more profound is the fact that this family found themselves entangled in Jesus’ story—and this is the closest any of the Herods came to sincerely embracing faith in Christ.

Drusilla

Agrippa II’s sister was initially married to Azizus, the priest-king of the Emesani dynasty. The Emesa people were known for their worship of the Syro-Roman God, Elagabalus. So this probably wasn’t the ideal relationship for a Jewish princess.

Drusilla caught the attention of Antonius Felix, the Roman procurator of Judea. She divorced her husband and married Felix.

She was with Felix during his first audience with Paul:

But some days later Felix arrived with Drusilla, his wife who was a Jewess, and sent for Paul and heard him speak about faith in Christ Jesus. But as he was discussing righteousness, self-control and the judgment to come, Felix became frightened and said, “Go away for the present, and when I find time I will summon you” (Acts 24:24–25).

Drusilla and Felix had a son, Marcos Antonius. Both Drusilla and her son died in Pompeii in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Along with Pliny the Elder, she was one of two significant figures reported to die in the eruption.

Berenice

A major celebrity in Agrippa’s court was his sister, Berenice. After a couple of failed marriages, Berenice went to live with her brother. It wasn’t too long that rumors began to spread of an incestuous relationship between the siblings.

In an effort to quell the rumors, she married another dignitary (Polemon II of Pontus), when that marriage failed, she ended up back in her brother’s home. The gossip about Agrippa II and Berenice’s relationship only got stronger. Part of that was due to the fact that Agrippa never married. Even more interesting is the fact that Josephus unflatteringly describes their relationship as incestuous—and Josephus was Agrippa II’s friend!

When the revolt against Rome broke out in Jerusalem, Berenice was in Palestine with her brother. She worked hard to get Rome to cease the violent oppression of the Jews. She had very little luck. As it turns out, she became lovers with Titus in 68 AD. Two years later, his army laid siege to Jerusalem. In the next four months, more than a million people died, and Jerusalem was utterly laid to waste.

Berenice ended up living in Rome as Titus’ consort. Public pressure forced Titus to send her away. After Titus became emperor, Berenice showed up again to pick up where they left off. But Titus sent her away, and no other records remain.

A dynasty fit for a serial

It’s hard to believe, but this is a fairly truncated post. To share all the intrigue and drama of the Herodian dynasty would take up twice as much real estate. The fact that no one has optioned the Herod family for a multi-season HBO drama should be considered negligence of the highest order.

But it’s incredibly rewarding to discover how many significant historical events and personalities lie at the borders of the gospel story. It’s a powerful reminder that Jesus’ story isn’t a remarkable tale that happened in a vacuum. It quietly played out amidst extraordinary world events.

And despite all of this political, sexual, violent drama that was happening on the world stage at the time, it’s the story of Jesus that everyone remembers.