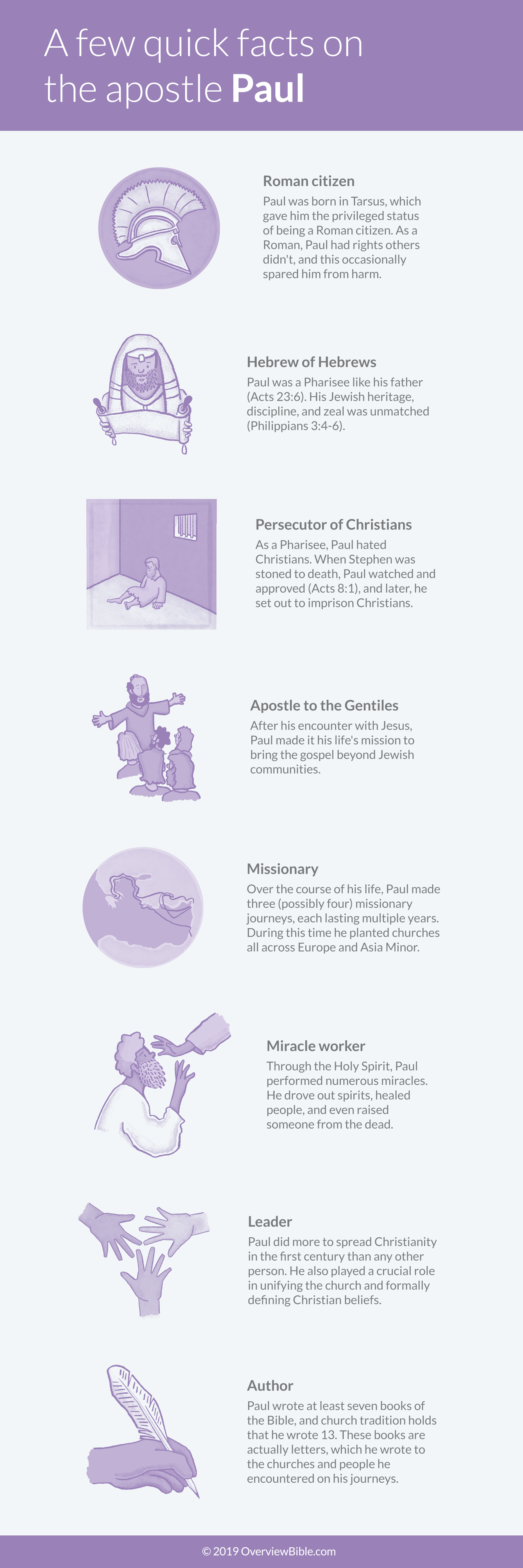

The Apostle Paul was one of the most influential leaders of the early Christian church. He played a crucial role in spreading the gospel to the Gentiles (non-Jews) during the first century, and his missionary journeys took him all throughout the Roman empire.

Paul started more than a dozen churches, and he’s traditionally considered the author of 13 books of the Bible—more than any other biblical writer. For this reason, Saint Paul is often considered one of the most influential people in history. He had a greater impact on the world’s religious landscape than any other person besides Jesus, and perhaps Muhammad.

But before he was known as a tireless champion of Christianity, Paul was actually known for persecuting Christians. The Book of Acts tells us that Paul was even present at the death of the first Christian martyr—where he “approved the stoning of Stephen” (Acts 8:1).

Over the last two millennia, countless books have been written about Paul and his teachings. In this beginner’s guide, we’ll explore the basics of what we know—and don’t know—about this important biblical figure.

Here’s what we’re going to cover:

- Who was Paul?

- Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus

- When did Paul live?

- Did Saul become Paul?

- Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles

- Paul’s missionary journeys

- How many times was Paul shipwrecked?

- Assassination attempts against Paul

- Paul’s appeal to Caesar

- Paul’s house arrest

- How much of the Bible did Paul write?

- How did Paul die?

Let’s begin! We’ll start with the basics.

Who was Paul?

Most of what we know about the Apostle Paul (also known as Saint Paul or Saul of Tarsus) comes from the writings attributed to him and the Book of Acts. However, there are also a couple of writings from the late first and early second centuries that refer to him, including Clement of Rome’s letter to the Corinthians.

A Hebrew of Hebrews

Before becoming a follower of Christ, Paul was a prime example of a “righteous” Jew. He came from a God-fearing family (2 Timothy 1:3), he was a Pharisee like his father (Acts 23:6), and he was educated by a respected rabbi named Gamaliel (Acts 22:3). His Jewish credentials included his heritage, discipline, and zeal.

In Philippians 3, he explains why if anyone ever had reason to believe that they could be saved by their adherence to Judaism, it was him:

“If someone else thinks they have reasons to put confidence in the flesh, I have more: circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; in regard to the law, a Pharisee; as for zeal, persecuting the church; as for righteousness based on the law, faultless.” —Philippians 3:4–6

He goes on to say that he considers this righteousness “garbage” next to the righteousness that comes from faith in Christ (Philippians 3:8–9).

Paul’s identity used to be rooted in his Jewishness, but after his dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus (more on that later) his identity as a Jew became secondary to his identity as a follower of Christ. He spent much of his ministry dismantling the idea that in order to have a saving faith in Jesus, Gentiles must first “become Jewish” by adopting the Mosaic Law. Being a “Hebrew of Hebrews” lent him credibility and expertise when speaking to Jewish audiences, and helped him speak into the Law’s inability to make people righteous.

A Roman citizen

Paul was born in Tarsus—a prosperous city in the province of Cilicia—which granted him Roman citizenship. This status gave him special privileges, and in some cases saved him from abuse (Acts 22:25–29).

In Acts 25, Paul was put on trial, and his accusers asked that he stand trial in Jerusalem, where they planned to ambush and kill him (Acts 25:3). Paul leveraged his Roman citizenship to demand Caesar himself hear his case (Acts 25:11), and procurator has no choice but to grant him this right. Unfortunately, the book ends before he gets to Caesar—because Paul’s story isn’t the point of Acts.

As a Roman citizen, Paul possessed a coveted status. Some, like the centurion in Acts 22:28, had to pay a lot of money to have it. Others served in the Roman military for 25 years to earn it. But Paul was born into this privilege. And instead of lording this status over everyone, he preached about a citizenship which everyone could choose to claim by accepting Jesus as Lord:

“But our citizenship is in heaven. And we eagerly await a Savior from there, the Lord Jesus Christ, who, by the power that enables him to bring everything under his control, will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body.” —Philippians 3:20–21

A persecutor of Christians

As a Pharisee, before his conversion to Christianity, Paul saw Christians (who were predominantly Jewish at the time) as a scourge against Judaism. From Paul’s perspective, these people were blaspheming about God and leading his people astray. He believed that Jesus was a mere man, and was therefore rightfully executed for claiming to be God.

And since Jesus’ followers kept spreading the idea that Jesus was God, Paul thought Christians were sinners of the worst sort.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Paul made his debut in the Bible as an intense persecutor of Christians. (Though he’s first mentioned by his Hebrew name, Saul—we’ll get to that soon.)

When Stephen was stoned to death for preaching the gospel, “the witnesses laid their coats at the feet of a young man named Saul . . . And Saul approved of their killing him” (Acts 7:58–8:1).

Later, Paul asked the high priest for permission to take Christians (known as followers of “the Way”) as prisoners:

“Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples. He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any there who belonged to the Way, whether men or women, he might take them as prisoners to Jerusalem.” —Acts 9:1–2

Paul’s notoriety as a persecutor of Christians made believers uncomfortable around him even after his baptism, and it took a while for them to believe that he’d really changed (Acts 9:26).

A leader in the early Christian church

After putting his faith in Jesus, Paul immediately began preaching publicly (Acts 9:20), and he quickly built a reputation as a formidable teacher (Acts 9:22). Throughout the rest of Acts, Paul is a prominent figure who plays a pivotal role in bringing the gospel to non-Jewish communities.

As we see from Paul’s own letters, he was highly respected in the increasingly scattered Christian communities, many of which he started himself. His letters frequently address problems and questions these churches wrote to him about.

An apostle to the Gentiles

While Paul’s status as a Pharisee and his intense devotion to the Law might have made him well-suited to preach to the Jews, Paul had a different calling. Before Paul ever preached the gospel, Jesus said, “This man is my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles and their kings and to the people of Israel” (Acts 9:15).

Fun fact: Paul did proclaim the name of Jesus to a Gentile king. In Acts 26, he shared the gospel with King Herod Agrippa II while he was on trial in Caesarea.

Paul’s calling as an apostle to the Gentiles was also reinforced by the original apostles. In his letter to the church in Galatians, Paul wanted the Galatians to know that they didn’t need to follow the Law of Moses to be saved. The gospel he preached to them was enough, and they just needed to have faith in Jesus. To prove his point, he told the Galatians that Peter (also known as Cephas), James, and John had nothing to add to Paul’s rendition of the gospel:

“As for those who were held in high esteem—whatever they were makes no difference to me; God does not show favoritism—they added nothing to my message. On the contrary, they recognized that I had been entrusted with the task of preaching the gospel to the uncircumcised, just as Peter had been to the circumcised. For God, who was at work in Peter as an apostle to the circumcised, was also at work in me as an apostle to the Gentiles. James, Cephas and John, those esteemed as pillars, gave me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship when they recognized the grace given to me. They agreed that we should go to the Gentiles, and they to the circumcised.” —Galatians 2:6–9

And if Peter, James, and John had nothing to add to what Paul preached, then why would the Galatians listen to someone else who said there was more they needed to do to be saved?

As an apostle to the Gentiles, not only did Paul need to engage the cultures he was trying to reach, but he had to protect these new believers from the weight of obligation that Jewish Christians often tried to impose on them. He was constantly trying to prove that the Gentiles didn’t need to adopt Jewish customs like circumcision in order to place their faith in Jesus and receive the Holy Spirit.

A missionary

Paul established numerous churches throughout Europe and Asia Minor, and was typically driven toward regions no one had evangelised to before:

“It has always been my ambition to preach the gospel where Christ was not known, so that I would not be building on someone else’s foundation” —Romans 15:20

The Book of Acts and Paul’s letters specifically record three missionary journeys to various cities throughout Europe and Asia, each lasting for several years. (We’ll discuss these more later, or you can read more about them now.)

Everywhere he went, Paul established new Christian communities and helped these fledgling believers develop their own leadership. He corresponded with these churches regularly and visited them as often as he could. Occasionally, they financially supported him so that he could continue his ministry elsewhere (Philippians 4:14–18, 2 Corinthians 11:8–9).

A miracle worker

Before Jesus ascended to heaven, he promised his followers they would receive power through the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:8). The Book of Acts records that the apostles performed miracles, and Paul is no exception. He healed people, cast out spirits, and even brought someone back from the dead. (Though to be fair, if Paul hadn’t talked him to sleep, the boy wouldn’t have fallen out of that window to begin with.)

Here are the miracles associated with Paul:

- He made a sorcerer go temporarily blind (Acts 13:11).

- He healed a man who had been lame since birth (Acts 14:8–10).

- He casted out a spirit that was annoying him (Acts 16:16-18).

- He healed people and cast out spirits through items he touched (Acts 19:11–12).

- He resurrected a young man named Eutychus (Acts 20:9-12).

- He was bit by a venomous snake and nothing happened to him (Acts 28:3-5).

- He healed a man with fever and dysentery (Acts 28:8).

To those who saw and heard Paul, these miracles proved his authority from God, just as Jesus’ miracles once demonstrated his (Mark 2:10).

Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus

One of the most remarkable aspects of Paul’s life is that as a young man, he was well-known for persecuting Christians, but by the end of his life, he’d endured significant persecution as a Christian. The Book of Acts and Paul’s own letters provide an account of how this dramatic change happened.

“Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples. He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any there who belonged to the Way, whether men or women, he might take them as prisoners to Jerusalem. As he neared Damascus on his journey, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice say to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’

‘Who are you, Lord?’ Saul asked.

‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting,’ he replied. ‘Now get up and go into the city, and you will be told what you must do.’

The men traveling with Saul stood there speechless; they heard the sound but did not see anyone. Saul got up from the ground, but when he opened his eyes he could see nothing. So they led him by the hand into Damascus. For three days he was blind, and did not eat or drink anything.” —Acts 9:1–9

This famous encounter is referred to as the road to Damascus, the Damascene conversion, and the Damascus Christophany (a vision of Christ distinct from his incarnation). On Paul’s way to round up some Christians as prisoners, Jesus stopped him dead in his tracks and crippled him with blindness.

But while Paul now knew the true identity and power of the one he had been persecuting, he had yet to learn Jesus’ grace and power to heal. And for that, he would need to meet a follower of Christ.

“In Damascus there was a disciple named Ananias. The Lord called to him in a vision, ‘Ananias!’

‘Yes, Lord,’ he answered.

The Lord told him, ‘Go to the house of Judas on Straight Street and ask for a man from Tarsus named Saul, for he is praying. In a vision he has seen a man named Ananias come and place his hands on him to restore his sight.’

‘Lord,’ Ananias answered, ‘I have heard many reports about this man and all the harm he has done to your holy people in Jerusalem. And he has come here with authority from the chief priests to arrest all who call on your name.’

But the Lord said to Ananias, ‘Go! This man is my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles and their kings and to the people of Israel. I will show him how much he must suffer for my name.’

Then Ananias went to the house and entered it. Placing his hands on Saul, he said, ‘Brother Saul, the Lord—Jesus, who appeared to you on the road as you were coming here—has sent me so that you may see again and be filled with the Holy Spirit.’ Immediately, something like scales fell from Saul’s eyes, and he could see again. He got up and was baptized, and after taking some food, he regained his strength.” —Acts 9:10–19

Paul spent the next few days with the very Christians he had come to capture, and he immediately began preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ—to the confusion of Christians and Jews alike. It would take time for Paul’s reputation as a Christian preacher to outgrow his reputation as a persecutor of Christians.

In his own accounts of his conversion, Paul says that Jesus appeared to him (1 Corinthians 15:7–8), and he claims that Jesus revealed the gospel to him (Galatians 1:11–16).

In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul appeals to the authority of eyewitness testimony, pointing out that Jesus appeared to many people including himself. In his letter to the Galatians, he builds the case that the Galatians can trust the gospel he presented them because it came directly from God, and the first apostles supported his message (Galatians 2:6–9).

This encounter on the road to Damascus completely redefined who Paul was, and it changed the purpose of his journey from silencing Christians to speaking out in support of them. Instead of taking away from their number, he added to it. And once Jesus redirected him, Paul continued on this trajectory for the rest of his life.

When did Paul live?

Scholars believe Paul was born sometime between 5 BC and 5 AD, and that he died around 64 or 67 AD. While he was a contemporary of Jesus, they never crossed paths—at least, not before Jesus died.

The first century was a tumultuous time for Christianity. The new religion was vulnerable, and it faced opposition everywhere from the Jews who believed it was blasphemy, and from the Romans who believed it challenged Caesar’s authority and created unrest. As a leader in the Jewish community, Paul saw the rapidly spreading Christian community as a threat, and he directly contributed to the persecution early Christians faced.

But after his encounter with Jesus, instead of stamping out Christianity, Paul stoked the flames of the faith wherever he went, at whatever the cost. More than any other person besides Jesus, Paul was the reason Christianity spread so far and so fast.

Did Saul become Paul?

It’s a common misconception that Paul “used to be Saul,” and that when Jesus called him, he renamed him Paul. You may have heard something like “Saul the persecutor became Paul the persecuted.”

But there’s no verse that says that. And Paul and Saul are actually two versions of the same name.

Shortly after Saul converts to Christianity, Luke tells us he’s also called Paul (Acts 13:9), and for the most part the rest of the Bible refers to him as Paul. But Jesus doesn’t refer to him as Paul, and he was still called Saul 11 more times after his conversion.

It’s true that in the Old Testament, God occasionally changed people’s names (Abram became Abraham in Genesis 17:5, and Jacob became Israel in Genesis 32:28) to represent significant changes in their identity. But that’s not what happened here.

The reality is that Saul was a Hebrew name and Paul was a Greek version of the same name. (Similar to how “James” is the Greek form of “Jacob,” and “Judas” is the Greek form of “Judah.”) As Paul began to evangelize Greek communities (and since most of the New Testament was written in Greek), it makes sense that we see the Greek version of his name most after his conversion.

Paul’s ministry to the gentiles

Of all the ways Paul affected Christianity, the biggest was arguably his role in spreading the gospel to non-Jewish communities. He certainly wasn’t the only apostle to do so, but he is known as the “apostle to the Gentiles” because that’s who Jesus specifically called him to minister to (Acts 9:15), he and the other apostles agreed that was his role (Galatians 2:7), and that was undeniably the focus of his ministry.

When Christianity emerged, it was often thought of as a Jewish sect—it built on Jewish teachings and beliefs, and because most Christians were also Jewish, many still followed Jewish customs and rituals established in the Law of Moses.

But Christianity was radically different from Judaism, and while many early Christians followed the Law, it wasn’t a prerequisite for believing in Jesus. The Law of Moses and the old covenant it bound them to had been replaced by Jesus’ new covenant, and the law of love (John 13:34-35).

For Paul, the apostles, and the early Christians, the Law (and specifically, circumcision) was one of the greatest theological issues of their day. First-century Jews had grown up believing the Law was central to their identity as God’s chosen people, and they struggled to fully grasp that Jesus rendered the Law obsolete (Hebrews 8:13).

The apostles agree with Paul

Paul constantly wrote to Gentile Christians to tell them not to worry about circumcision (as you can imagine, uncircumcised adults were rightfully freaked out by the idea that they’d have to do this), and in Acts 15, the apostles met with Paul and Barnabas to officially settle the matter, because pockets of Jewish Christians were continuing to tell Gentiles to get circumcised.

Peter argued that God hadn’t discriminated between Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians because he’d given them both the Holy Spirit, and if in the entire history of Judaism no one had been able to keep the Law (except Jesus), then why would they put that burden on the Gentiles (Acts 15:7-11)?

After listening to everyone, the Apostle James concluded:

“It is my judgment, therefore, that we should not make it difficult for the Gentiles who are turning to God. Instead we should write to them, telling them to abstain from food polluted by idols, from sexual immorality, from the meat of strangled animals and from blood. For the law of Moses has been preached in every city from the earliest times and is read in the synagogues on every Sabbath.” —Acts 15:19–21

If you’ll notice, the apostles didn’t decide that Gentiles should follow “the most important” commandments, or the Big Ten, or anything like that. Instead, they essentially instructed Gentiles be culturally sensitive to their Jewish brothers and sisters, because the Law was respected and observed by Jews everywhere.

But despite the apostles’ agreement that Gentiles didn’t have to adopt Jewish customs to be Christian, Jewish Christians still saw law-observing Christians as superior, and even Peter let himself get pressured into playing favorites.

Paul wasn’t going to let that slide.

Paul confronts Peter

After he received a vision (Acts 10:9–16), Peter was one of the first apostles to specifically advocate for sharing the gospel with Gentiles. But as the Gentiles joined the church, Paul noticed that Peter still treated Gentile Christians differently in order to save face with those who still valued the law.

So Paul called him out on it.

“When Cephas came to Antioch, I opposed him to his face, because he stood condemned. For before certain men came from James, he used to eat with the Gentiles. But when they arrived, he began to draw back and separate himself from the Gentiles because he was afraid of those who belonged to the circumcision group. The other Jews joined him in his hypocrisy, so that by their hypocrisy even Barnabas was led astray.

When I saw that they were not acting in line with the truth of the gospel, I said to Cephas in front of them all, ‘You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?

‘We who are Jews by birth and not sinful Gentiles know that a person is not justified by the works of the law, but by faith in Jesus Christ. So we, too, have put our faith in Christ Jesus that we may be justified by faith in Christ and not by the works of the law, because by the works of the law no one will be justified.’” —Galatians 2:11–16

Paul goes on to say that “if righteousness could be gained through the law, Christ died for nothing!” (Galatians 2:21). And as he explained earlier in his epistle to the Galatians, Peter, James, and John already agreed with him: the Gentiles did not need to follow the Law of Moses, and Jewish Christians were not better or superior than Gentile Christians because they did follow the Law.

Not a fun fact: Even though Paul argued that Christians didn’t need to be circumcised in Acts 15, he circumcised Timothy in the very next chapter “because of the Jews who lived in that area” (Acts 16:1–3).

Paul’s missionary journeys

Acts records three missionary journeys that took Paul throughout Asia Minor, Cyprus, Greece, Macedonia, and Syria. Some scholars argue there was a fourth missionary journey as well. In each of these, Paul and his companions set out to bring the gospel to Gentiles, and they establish the churches Paul wrote to in his epistles (as well as many others).

In some cases, Paul spent well over a year in the cities he preached to, living with the believers there and modeling a lifestyle of imitating Christ. Over the course of his life, Paul likely traveled well over 10,000 miles to spread the gospel.

Paul’s first missionary journey (Acts 13–14)

Paul’s first journey began in Antioch with a calling from the Holy Spirit (Acts 13:2–3). He left the church with Barnabas and a man named John (also called Mark, believed to be the author of the Gospel of Mark), and together they sailed to Cyprus, an island in the Mediterranean.

Here Paul performed his first miracle, perhaps inspired by his own conversion on the road to Damascus: he blinded a sorcerer who opposed their attempts to evangelize a proconsul (Acts 13:10–12).

Then they sailed to Perga in Pamphylia, where John Mark parted ways with Paul and Barnabas (this became a point of tension between Paul and Barnabas later). From there, Paul and Barnabas went to Psidion Antioch, a city in the mountains of Turkey.

In Psidion Antioch, Paul and Barnabas entered a synagogue during the Sabbath, and Paul preached the gospel to Jews and Gentiles alike. They were invited to come speak on the following Sabbath, and when they did, most of the city attended. Many of the Jews in attendance grew angry and tried to stop them, but the Gentiles were receptive to their message.Paul and Barnabas ultimately left Psidion Antioch due to persecution, and traveled to another Turkish city called Iconium. They spent “considerable time there” (Acts 14:3), and the city became increasingly divided: some Jews and Gentiles supported them, and others reviled them. Those who opposed Paul and Barnabas started a plot to stone them, but they caught wind of it and fled to the Lycaonian city of Lystra.

There, Paul performed another miracle: he healed a man who had been lame since birth (Acts 14:8-10). The people who saw this thought Paul and Barnabas were gods, and attempted to make sacrifices to them even as Paul and Barnabas tried to convince them not to.

Some of the people who opposed them in Psidion Antioch and Iconium followed them to Lystra, and they stirred up the crowd against them. They stoned Paul and left him for dead outside the city. Then he got up and went back in. The next day they left for Derbe, another Lycaonian city where they “won a large number of disciples” (Acts 14:21).

From Derbe, Paul and Barnabas looped back through the cities they’d already preached to, encouraging the new believers there and appointing elders for each church.

Paul’s second missionary journey (Acts 15:36–18:22)

After staying in Antioch for awhile, Paul asked Barnabas to go with him to visit the churches they’d established together. Barnabas wanted to bring John Mark again, but Paul didn’t think John Mark should come since he’d abandoned them before. So Paul and Barnabas parted ways: Barnabas took John Mark to Cyprus, and Paul took a man named Silas to Syria and Cilicia.

Paul and Silas travelled through Derbe and then Lystra, where they picked up a believer named Timothy (this is the Timothy Paul writes to in 1 Timothy and 2 Timothy). Together they traveled from town to town and told people what the apostles had decided at the Council of Jerusalem where James told Gentile Christians not to worry about circumcision, which was pretty ironic, because Paul had just circumcised Timothy (Acts 16:3).

The Holy Spirit kept Paul and his companions from preaching in the province of Asia, so they went to Phrygia and Galatia (where they planted the church Paul would later write to in Galatians), eventually making their way to Troas.

Fun fact: “Asia” used to refer to a very specific region in part of what we know as Turkey today, but westerners began using the name to describe pretty much anything east of them, until they eventually used it for the whole continent.

Paul had a vision which led the group to Macedonia, and interestingly, here the author of Acts begins to include themself in the story “After Paul had seen the vision, we got ready at once to leave for Macedonia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to them” (Acts 16:10, emphasis added).

They wound their way through several provinces to arrive in Philippi, the main city in Macedonia. Here they met with a group of women, including a wealthy cloth dealer named Lydia. After they baptized Lydia and her household, she invited them to stay at her house. These were the first members of the church Paul writes to in Philippians.

During their time in Philippi, a spirit that possessed a local slave girl was bothering Paul, so he cast it out of her (Acts 16:18). Normally people are ecstatic when that happens, but the slave girl’s owners had been making money off of her because of the spirit, so they were pretty mad. They got everyone riled up against Paul and Silas and managed to convince the local authorities to have them beaten and imprisoned.

While Paul and Silas were in jail, there was an earthquake, and the prison doors opened and everyone’s chains came loose, but no one tried to escape. Paul and Silas shared the gospel with the jailer, and once they were freed, they returned to Lydia’s house, and then left for Thessalonica.

For three Sabbaths, Paul taught in the synagogues and established the group of believers that he would later write to in 1 Thessalonians and 2 Thessalonians. He gained many followers, but those who opposed him started a riot and threatened his supporters, so the believers sent him on to Berea.

The Berean Jews “received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true” (Acts 17:11). Unfortunately, some of those who opposed Paul and his companions in Thessalonica heard he was in Berea, so they came and started causing trouble. Paul left to Athens. Silas and Timothy stayed behind, but would catch up later.

The Athenians were accustomed to discussing new ideas, and they’d never heard the message Paul preached before, so they were intrigued and debated with him. Some of his listeners became believers, and then he left for Corinth.

Paul stayed in Corinth for a year and a half, preaching in the synagogues and gaining both Jewish and Gentile followers from a range of social statuses, forming the group of believers he would later write to in 1 Corinthians and 2 Corinthians. He stayed with two named Aquila and Priscilla, who were tentmakers, like him. Silas and Timothy rejoined him here.

The Jews who opposed Paul tried to bring charges against him based on Jewish law, but the Roman proconsul wasn’t interested in hearing their case. Paul left with Priscilla and Aquila and journeyed to Ephesus.

In Ephesus, Paul went into the synagogue and reasoned with the Jews and promised to return if he could. Then he made his way back to Jerusalem and Antioch, where his second journey ended.

Paul’s third missionary journey (Acts 18:23–20:38)

Paul began his third missionary journey by returning to Galatia and Phrygia, where he continued building up the churches he’d established.

From there, Paul traveled back to Ephesus, where he encountered some believers who weren’t familiar with the Holy Spirit, because they’d been taught by Apollos, who didn’t have a complete grasp of the gospel at the time.

Paul remained in Ephesus for more than two years, and during that time he transitioned from teaching in the synagogue to discussing the gospel in the lecture hall of Tyrannus. Acts records that “all the Jews and Greeks who lived in the province of Asia heard the word of the Lord” (Acts 19:10).

During this time, Paul did many miracles, and even things he touched were reported to have healed people (Acts 19:12). After a dangerous evil spirit claimed to know Jesus and Paul, people flocked to Paul and his followers and the church grew quickly.

Around this time, Paul decided to head to Jerusalem, so he journeyed through Macedonia and Achaia, and made plans to stop in Rome. Meanwhile, Ephesus was in uproar, because Christianity’s explosive growth had stifled businesses that relied on idol worship.

The city was on the brink of rioting, and Paul wanted to return to help his companions, but the city clerk managed to de-escalate the situation without him. (Which was a good thing, because those business owners were pretty mad at Paul, and they probably would’ve killed him.)

Paul spent three months in Greece, then returned to Macedonia to avoid some people who were plotting against him. In Troas (a city in Macedonia), Paul was teaching in an upper room when a young man fell asleep and tumbled out the window, falling to his death. Paul revived him, then left.

In a rush to reach Jerusalem, Paul bounced from Troas to Assos, Mitylene, Chios, and finally Miletus, where he asked the elders from Ephesus to meet him. After encouraging them, he boarded a ship and returned to Jerusalem, even after numerous Christians warned him not to go there.

Paul’s fourth missionary journey (?)

Some argue that Paul made a fourth missionary journey as well, since some of his letters refer to events and visits that may not be accounted for in Acts. This largely depends on whether Paul was imprisoned in Rome once, or twice, which his letters are ambiguous about.Paul suggested he would travel to Spain (Romans 15:24), but he provides no record of this journey in his letters. However, early church fathers claimed Paul did, in fact, travel to Spain.

In his letter to the Corinthians, first-century church father Clement of Rome said Paul “had gone to the extremity of the west,” which at the time presumably meant Spain. Fourth-century church father John of Chrysostom said “For after he had been in Rome, he returned to Spain, but whether he came thence again into these parts, we know not.” And Cyril of Jerusalem (also from the fourth century) wrote that Paul “carried the earnestness of his preaching as far as Spain.”

Still, scholars can’t be sure that Paul did make this fourth journey, as the primary sources for his other three journeys (Acts and the epistles) don’t give us an explicit account of it.

How many times was Paul shipwrecked?

On many of Paul’s journeys, he travelled by boat. As you can imagine, boats weren’t nearly as safe in the first century—especially on long voyages. In his second letter to the Corinthians, which was likely written before his final trip to Jerusalem, Paul claims he was shipwrecked three times:

“Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I was stoned. Three times I was shipwrecked; a night and a day I was adrift at sea;” —2 Corinthians 11:25

There’s no other record of these wrecks in the epistles or in Acts, but Acts 27 does record a fourth shipwreck in far more detail. On Paul’s way to trial in Rome, his boat encounters a brutal storm and dangerous waters. The soldiers took drastic measures, but an angel spoke to Paul, and he encouraged and advised them along the way.

Assassination attempts against Paul

During his ministry, Paul made a lot of people mad. On six occasions in Acts, Jews and Gentiles alike made plans to murder him—and one of those times, they stoned him and left him for dead.

Only counting the times the Bible explicitly says they planned to kill him, not just attack or harm him, here they in sequential order.

1. In Damascus

Just after his conversion on the road to Damascus, Paul began preaching in the synagogues. After several days, people began planning to kill him, and they watched the city gates day and night. His followers smuggled him in and out of the city in a basket (Acts 9:23–25).

2. In Jerusalem

When Paul left Damascus, he went to Jerusalem and tried to join the disciples there. He began debating with Hellenistic Jews, and they tried to kill him, so the Christians took him to Caesarea an sent him home to Tarsus (Acts 9:26–30).

3. In Iconium

Paul and Barnabas spent a long time in Iconium, and the city was divided: some people supported them, and others hated them. Jews and Gentiles alike plotted to stone them, and when Paul and Barnabas found out, they fled to Lystra (Acts 14:4–6).

4. In Lystra

After Paul healed a man in Lystra, people thought he and Barnabas were the gods, Zeus and Hermes, and attempted to sacrifice to them. But then some Jews came from Antioch and Iconium, and convinced this crowd to actually stone Paul. They thought they killed him, so they left him outside the city gate. (He was still alive.) Then he and Barnabas left (Acts 14:8–20).

5. In Jerusalem (again)

After Paul insulted the high priest and sparked an intense theological debate between the Sadducees and Pharisees, a group of more than 40 men took a vow not to eat or drink until they killed Paul (Acts 23:12–13).

Their plan was to have a centurion send Paul to the Sanhedrin for questioning, and then kill him on the way. But someone warned the centurion of the plan, and instead, he rounded up nearly 500 soldiers to take Paul to the governor in Caesarea.

6. In Caesarea

Years later, Paul was still being held prisoner, and there was a new proconsul named Porcius Festus was in charge. Paul’s accusers requested that Paul be sent back to Jerusalem “for they were preparing an ambush to kill him along the way” (Acts 25:3).

Festus refused, and told them to make their case in Caesarea, where Paul used his privilege as a Roman citizen to make a bold request.

Paul’s appeal to Caesar

When Paul was first imprisoned in Caesarea, he made his appeal to Governor Felix, then waited two years in prison with no progress. (Governor Felix strung him along because he wanted the Jews to like him, and he hoped Paul would bribe him.)

Porcius Festus succeeded Felix and after hearing Paul defend himself, he asked Paul if would be willing to stand trial in Jerusalem.

Tired of his case dragging on to appease his Jewish accusers, Paul claimed his right as a Roman to appeal to Caesar:

“I am now standing before Caesar’s court, where I ought to be tried. I have not done any wrong to the Jews, as you yourself know very well. If, however, I am guilty of doing anything deserving death, I do not refuse to die. But if the charges brought against me by these Jews are not true, no one has the right to hand me over to them. I appeal to Caesar!”

After Festus had conferred with his council, he declared: “You have appealed to Caesar. To Caesar you will go!” —Acts 25:10–12

Unfortunately, the Book of Acts ends before Paul’s trial before Caesar. But before he leaves Caesarea, another ruler—King Herod Agrippa II—hears his case, and tells Festus:

“This man could have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar.” —Acts 26:32

Perhaps Paul hoped appealing to Caesar would finally put an end to his case, but unfortunately, it dragged them out even further.

Or . . . perhaps it was a strategic move on Paul’s part to testify about Christ to the leaders of the Roman empire. Having Caesar’s court and the Roman justice system as his captive audience might have been Paul’s play all along.

Paul’s house arrest (Acts 28:14–31)

By appealing to Caesar, Paul forced Festus to send him to Rome to await trial. When he finally arrived, “Paul was allowed to live by himself, with a soldier to guard him” (Acts 28:16). Here, Paul preached freely to the Jews in Rome for two years. Scholars believe this is likely when he wrote his letter to the Philippians, because he references being in chains (Philippians 1:12–13).

The Book of Acts ends with Paul under house arrest, and we don’t learn much more about the situation from the epistles, and scholars debate about whether or not Paul was ever released from house arrest. Some argue that his letters speak of his imprisonment in the past tense and make references to things that could have only occurred after his house arrest.

For example, in 2 Timothy (believed to have been written shortly before his death) he appears to reference a recent trip to Troas (2 Timothy 4:13), which would’ve been impossible if he’d already been imprisoned in Caesarea for more than two years before his house arrest in Rome.

Whether or not Paul made a fourth missionary journey (possibly to Spain) largely depends on if he was imprisoned in Rome once or twice.

How much of the Bible did Paul write?

The Apostle Paul is traditionally considered the author of 13 books of the New Testament. While Moses still holds the title for writing the most words in the Bible (traditionally), Paul wrote the most documents. (Well, unless you count each individual Psalm as a document, in which case David wins.) The books attributed to him include:

- Romans

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Galatians

- Ephesians

- Colossians

- 1 Thessalonians

- 2 Thessalonians

- 1 Timothy

- 2 Timothy

- Titus

- Philemon

These books are actually letters—or epistles—which were written to churches Paul planted and people he presumably encountered on the missionary journeys we see in the Book of Acts. The letters reference many of the events recorded in Acts, which scholars have used to construct more clear timelines of Paul’s life and ministry.

But not everyone agrees that Paul wrote all of these letters. Most scholars (critical and conservative) believe that Paul did write seven of them: Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon. But the remaining six letters have raised some questions, and scholars debate whether or not they can really be attributed to Paul.

Colossians makes some questionable references which Paul doesn’t make anywhere else (he calls Jesus “the image of the invisible God” in Colossians 1:15), and which align more with later Christian theology (like that found in John’s gospel), so some have argued it was written by Paul’s followers after his death.

Ephesians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus all have very different styles than Paul’s other letters. This could mean Paul simply had a different purpose in writing them, or that Paul’s writing style changed over the course of his ministry, but the epistles to Timothy and Titus also have very different vocabulary and even theology than we see in other Pauline writings.

Many Christians would be surprised to learn that these academic debates are even happening, because these letters are all signed by Paul. But scholars argue that these epistles are actually pseudepigrapha: writings that claim to be written by someone who was not the actual author.

Some pseudepigrapha is harmless, produced out of convenience, necessity, or accepted practices of the time (such as a student writing on behalf of a teacher, with the approval and authority of the teacher). Others, like many of the Gnostic gospels, were blatant forgeries written to advance a theological position.

At worst, someone wrote these letters and deceitfully signed Paul’s name to make them more authoritative. But many scholars believe it’s more likely that Paul asked his companions to write them, told them what to write, and signed his name. This would explain differences in style and vocabulary without really losing the letters’ authenticity.

Did Paul write the Book of Hebrews?

Almost all scholars today agree that Paul didn’t write Hebrews, and the true biblical author remains unknown. However, the early church assumed the letter was written by Paul, and even included it in early collections of his writings. This was contested as early as the second and third centuries, but for more than a millennia the church largely believed Paul wrote it.

Early Christian writers even suggested possible alternative authors. Tertullian (c. 155–240 AD) proposed that it was written by Barnabas. Hippolytus (c. 170–235 AD) believed it was Clement of Rome.

The father of church history, Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260–339 AD) noted that “some have rejected the Epistle to the Hebrews, saying that it is disputed by the church of Rome, on the ground that it was not written by Paul” (Church History). But he himself held the view that Paul wrote the letter in Hebrew and simply chose not to sign it, and then Luke translated it to Greek.

Today, it’s not really even up for debate. Donald Guthrie wrote in his New Testament Introduction that “most modern writers find more difficulty in imagining how this Epistle was ever attributed to Paul than in disposing of the theory.”

We will likely never know who really wrote Hebrews. But we can be pretty confident that it wasn’t Paul.

The Beginner’s Guide to the Bible gives you an overview of what the Bible is, what it’s for, and what it’s all about. It explores how each of the Bible’s 66 books fit into the big picture, and you’ll walk away with enough knowledge to have a thoughtful conversation about the Bible with a pastor, an atheist, or anyone else.

The Beginner’s Guide to the Bible gives you an overview of what the Bible is, what it’s for, and what it’s all about. It explores how each of the Bible’s 66 books fit into the big picture, and you’ll walk away with enough knowledge to have a thoughtful conversation about the Bible with a pastor, an atheist, or anyone else.

How did Paul die?

The Bible doesn’t tell us how Paul died, but numerous early church fathers wrote that he was martyred—specifically, he was beheaded, probably by emperor Nero, which would mean it had to be sometime before 68 AD.

Clement of Rome provided the earliest surviving record of Paul’s death in his letter to the Corinthians (known as 1 Clement), where he mentions that Paul and Peter were martyred.

An apocryphal work from the second century known as The Acts of Paul says that Nero had Paul decapitated. And in 200 AD, Tertullian wrote that Paul’s death was like John the Baptist’s (decapitation). Other early Christian writers support these claims and provide some additional details like where it happened (Rome) and where he was buried (the Ostian Way at Rome).

Paul’s remains

In 2002, archaeologists found a large marble sarcophagus near the location Jerome and Caius described. It had “PAULO APOSTOLO MART” (Paul apostle martyr) written on it. No one ever opened the sarcophagus, but using a probe and carbon dating, archaeologists estimated that the remains inside were from the first or second century. The Vatican claims these are in fact the remains of Saint Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles.

Paul: apostle, missionary, writer, martyr

From the moment he became a believer in Christ, Paul’s life was transformed. While Jesus didn’t give Saul a new name, he did give him a new purpose: one that redefined his life. Instead of persecuting Christians, Paul was called to be persecuted as one of them.

Despite never witnessing Jesus’ ministry, Paul arguably contributed more to the growth of the Christian movement than any other apostle. He laid the foundation for missions work that has continued around the world today, and through his life he modeled evangelism, discipleship, perseverance, and suffering—for the Christians who knew him, and for every believer today.

It’s Sunday morning and my grandson Paul is on his honeymoon. He is named after his great grandfather my dad a caring man that touch many lives especially young boys trough being a Boy Scout master for over forty years. As I sat here this morning thinking of my grandson Paul I decided I wanted to learn more about Paul in the Bible that he was named after through generations and I must say I have not only learned a great deal but your writing style was wonderful even though some of the parts of his life pulled at my heart I then focused on all the amazing things he did to serve our awesome God! A new found reader, Paul’s Mima

Thank you for such an informative piece of writing and breaking down of scriptures, with supporting ref’s.

This has help me understand and see the word in a different light, especially Paul’s works.

Absolutely love it.

Thanks, keep up the good work.

God Bless

There is no book of Paul just his letters, however it is very clear that God used him as a post disciple of Christ Jesus to solidify the truth. Paul’s truth moves us into Revelations as the Church of Ephesus is taken into account of the last days. My fellow Christians we are to ensure other Christians to live up to our heavenly calling.

What a wonderful synopsis of Paul. I am enthralled.

As a GA in my teens I wrote and mapped Paul’s Missionary Journeys. Wonderful maps. I will have to reread this several times to add to my thinking and understanding. Paul was born a Jew with Roman citizenship. He had an elite education. Like his father he was a Pharisee but grafted into Christianity through conversion.

Love the name clarification:Paul and Saul.

Excellent information in a very understandable way.

I like the map you two put together; it’s clean and crisp looking,

and very helpful with where the pertinent towns and country locations.

I’m in the process of putting together a book about the three Pastorals and was wondering if you might allow me to use your map as the book cover (front and back – wraparound cover). I would, of course, give you credit for having created the map – cover sheet. I’m just brain-storming here, with you, I’ve been thinking about using such a cover sheet for some time now, and your map just strikes me as being the best one I’ve seen.

Please get back with me, even if you’re not interested in my idea,

Thank you,

Robin Riley

Glad you like the maps! You’re welcome to include them in a blog post or even a figure within your book with attribution, but we don’t want these to be used as a book cover. If you like the style, you’re also welcome to connect with the artist (Liz Donovan) on dribble or via email.

Dribbble: https://dribbble.com/lizlovesdesign

Email: lizlovesdesign@gmail.com

I really enjoyed your history of Pauls life , ministry , journeys etc ,. I am excited to see what you give us next …

Some sources might help your case there, friend.

For my part, I’m not surprised that it would take some time to go from “breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples” (Acts 9:1) to risking your own murder for the sake of making disciples. That’s a huge shift—even a three-year turnaround sounds pretty speedy to me. Just overcoming the feelings of guilt alone would be a time-consuming undertaking.

Thank you so much for the Interesting history of Paul and the guide

God bless you

That is a rather good summary … Well Done!

Thanks very much for the guide