Why would you begin the story of Jesus (and the entire New Testament) with a boring list of more than 40 names?

Well, as is often the case with Scripture, there’s a lot bubbling below the surface—including a few interesting “Easter eggs” that an ancient Jewish reader who was familiar with the Old Testament might notice when reading Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus.

Welcome to the New Testament?

If you’re familiar with The Bible, then you know that the Bible falls into two large sections:

- The Old Testament, which looks at the relationship between God and the people of Israel. This is where God makes a lot of promises to Israel, including the promise of a coming king, who is called the Messiah, who would redeem Israel and lead the nations in an era of peace and justice.

- The New Testament, which follows the life of Jesus Christ, whom the Christians, Jesus’ followers, believed is that king: the Messiah.

And right at the beginning of the New Testament, we see the Gospel of Matthew. And it opens with the line, “The genealogy of Jesus, the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham.”

This list of names might seem boring to a modern reader. But to someone who’s really familiar with the Old Testament, there are some really cool “Easter eggs” that you can find in this that make hints at what Matthew‘s going to cover in the rest of his gospel.

(Remember: Matthew’s story doesn’t end here. This is just the beginning. After this, we start to read about the birth of Jesus and then his miracles and teachings, and ultimately his death and resurrection. So this is just the overture.)

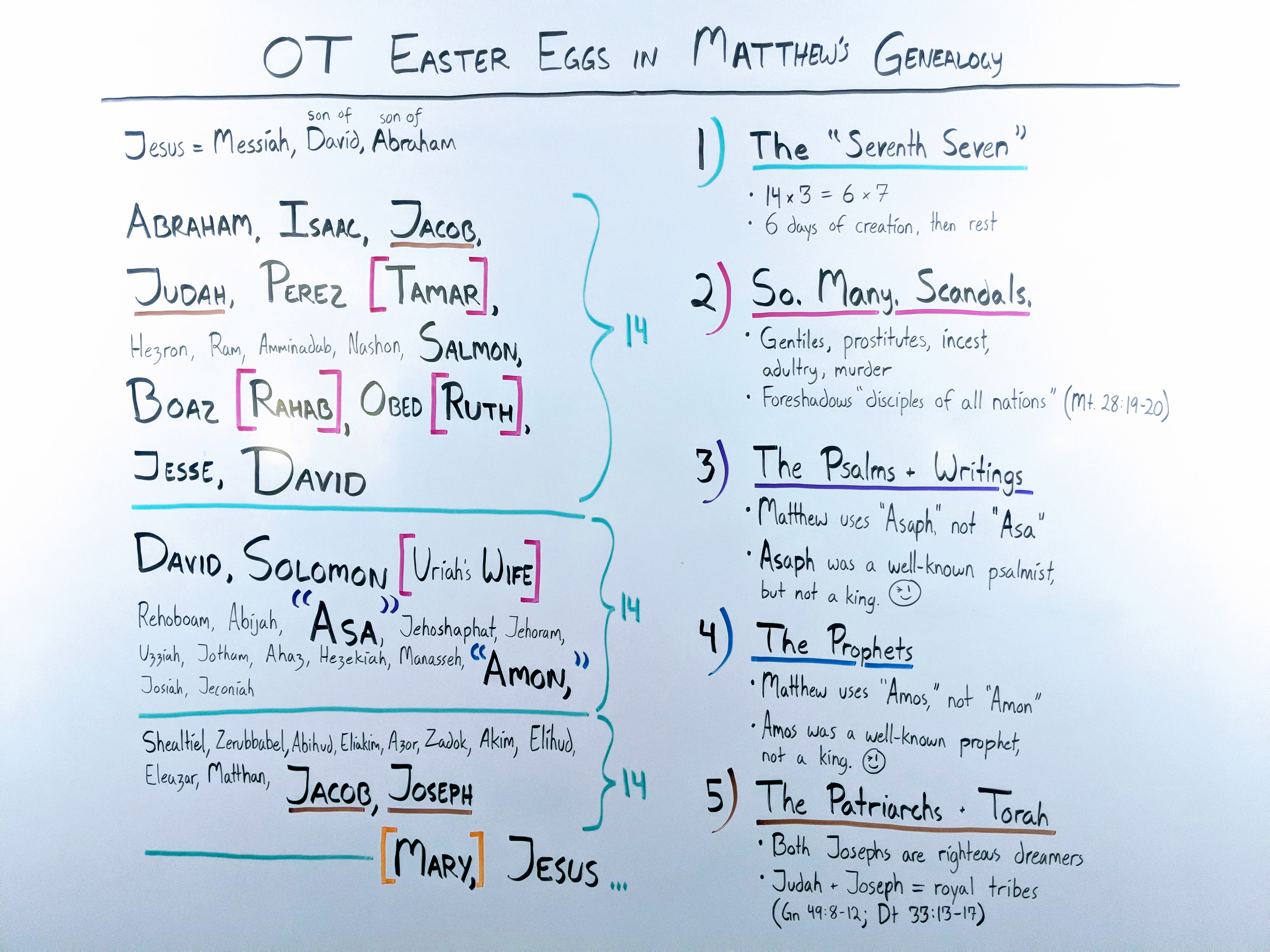

1. Matthew puts the reader in the “seventh seven”

One thing that is very interesting is the way Matthew groups these names. We see a group of 14 generations, another group of 14, and then another group of 14.

Now if you’re familiar with The Bible, you know that the number seven is pretty prominent. Right at the beginning of the Bible, inthe book of Genesis, God creates the world in six days and then rests on the seventh. And that becomes a pattern that the people of Israel follow week to week. They work six days and then they rest for one. (That seventh day is called the Sabbath.)

Now for just a little math:

- 14 is 7 +7, so each 14 is a pair of seven generations

- Matthew gives us three sets of 14 generations

- Which gives us a total of six “sevens”

The people reading his gospel would’ve been after that last generation, which would put them in the following generational bracket: the “seventh seven.” So, just like in the Genesis story of six days of creation culminating in a time of rest, we have six periods of time culminating in the time of the Messiah—a king who was supposed to bring Israel and the nations peace, justice, and rest.

2. Matthew specifically references OT scandals

If you read through these names, you’re going to find certain mothers called out. The Jews traced their lineage through the fathers, but in Matthew’s genealogy, he recognizes some of the mothers. So we’ll see, “Perez, whose mother was Tamar,” and “Boaz, whose mother was Rahab.”

But here’s the deal—most of these mothers represent things that the Jews wouldn’t expect in the introduction of a Messianic King.

- Tamar was Perez’ mother … but also his sister-in-law. (A twisted story you can read all about in Genesis 38.)

- Rahab was a Canaanite prostitute, someone who, under the Law of Moses, shouldn’t exist in the Jewish community.

- Ruth was a Moabite, a people group who wasn’t allowed to worship at the Jewish temple.

- Bathsheba isn’t even mentioned by name. Instead, we get “Uriah’s wife.” David murdered the Uriah the Hittite, one of his famous mighty men, and took Bathsheba for himself.

That’s not the most flattering sort of information that you want to be bringing into people’s mind when they’re reading the genealogy of a king.

So what does that tell us about the story that Matthew is going to share? Well, in the rest of Matthew’s gospel, we’re going to find that Jesus subverts the Jews’ expectations when it comes to their Messiah. He’s going to challenge the way they think about the Sabbath, giving, obedience, and the kingdom of heaven itself. The Jews expected a Messiah who would liberate Israel and rule the other nations. And yet Matthew introduces Jesus by highlighting how his bloodline includes other nations.

It’s a clue that points to the very end of Matthew’s gospel. Jesus rises from the dead and he tells his disciples to go and make more followers of him from all the nations. Not just Israel. And so we can see right at the beginning a glimpse of where Matthew’s taking us. Jesus is going to surprise and offend a lot of the Jewish leaders’ expectations with his good news of this very inclusive gospel. He’s a great Messiah, but a lot of people don’t recognize him because they’re expecting something different.

3. “Asa” is a nod to the Psalms

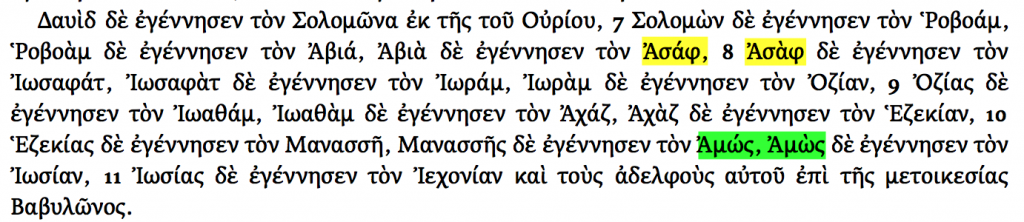

Let’s look at something else that someone who was very familiar with the Old Testament might see when they’re looking at Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus. If you’re reading the genealogy in your English Bible, then you’re going to come to that second bracket. And you’re gonna see David, Solomon, Rehoboam, Abijah, and so on.

When you see “Asa” in your English Bible, stop. Because while Asa was the name of the actual king of Jerusalem, Matthew doesn’t write the name Asa. Matthew writes another name. If you look it up in Greek, you’ll see that Matthew actually uses the word “Asaph,” not Asa. Asaph was a well-known psalmist. He penned several of the Psalms. Someone familiar with the Old Testament would know this.

This is almost like a wink to the audience, because we’re going to see Jesus as the fulfillment of all Scripture. And so Matthew was bringing in the Psalms and the wisdom literature that the Hebrews already had in Scripture and saying this points to Jesus as the Messiah too.

4. “Amon” brings in the prophets

Now we see something really similar next up. And that is when we get to the name of Amon. Amon was the name of a king. But it’s the same situation as with Asa: in the English Bible we see “Amon,” but in Greek, Matthew doesn’t say Amon. He uses another name. He uses the name Amos.

Now if you’re familiar with the Old Testament, you know there’s a book of the Old Testament named Amos. It’s named after a prophet. A prophet who spoke out to the kingdom of Israel. And so someone reading this who was familiar with the Old Testament would immediately think of the prophets—because there was no king named Amos.

Matthew was giving another wink to the audience. He’s saying, “Hey, not only am I going to show you that Jesus is the culmination of the psalms and the writings. But also, Jesus is the one the prophets spoke about.” Matthew brings in those prophecies that are fulfilled time and time again as he introduces this gospel. But he’s giving us a hint right in the genealogy.

Here’s a screenshot from the NA 27th Ed. Greek New Testament. “Asaph” is highlighted in yellow, “Amos” in green.

5. Joseph and Judah

The Tanakh, or the Old Testament of Jesus time, was divided into three parts. You had the Torah first, and then you had the Prophets, and then you had the Writings (which included the Psalms). Matthew has given us a few clever nods to the Prophets and the Writings—so, do we see anything from the Torah in here?

We sure do.

Not only do we already have the reference to creation with six sevens and the time of the Messiah, we also see a really cool combination of certain names in this genealogy. Now way back in Genesis, which is part of the Torah, we meet a man named Jacob. And Jacob has 12 sons. Each of these sons becomes the patriarch of a subgroup of the nation of Israel called a tribe (that’s where we get the 12 tribes of Israel).

Now two of those sons stood out and two of those tribes had a royal reputation from very, very early on in the Bible. In fact, in the Book of Genesis when Jacob is blessing his son, Judah, he says, “The scepter will never depart from Judah.” Jacob says that Judah’s brothers will bow down to him (Gn 49:8, 10). Which we see in David. David’s from the line of Judah and David was the greatest king of Israel.

But in that same Genesis blessing Jacob refers to Joseph as “the prince among his brothers” (Gn 49:26). Later on in the Torah, Moses repeats this idea (Dt 33:13-17).

And so we have two sons of Jacob in the Torah that are mentioned as having this royal destiny. We see that in this genealogy too. So right up top, we have Jacob and then Judah. And then right at the end, right before Jesus is introduced, we have Joseph. Now we all know about Mary and Joseph. But guess what Joseph’s father’s name is?

Jacob.

So we have Jacob and Judah. And then we have Jacob and Joseph. Really, really interesting to see that woven in here because that brings in bits of the Torah and Jewish history when we’re looking at who’s going to be the king of the Jews.

Another really fun tidbit is that Joseph in the Old Testament was known as a dreamer. He had dreams and he could interpret dreams. The person who has the most recorded dreams in the Bible is Joseph, who was called the father of Jesus.

Right at the beginning of the New Testament, we have the psalms, the prophets, and the Torah. All three elements of the Old Testament combining to point to Jesus as the Messiah and that promised king. Not only of Israel, but of all nations. And that’s why beginning Matthew and the entire New Testament with this names is such a fascinatingly great idea. Matthew ties together the entire Old Testament and says it all just points straight to Jesus. And then he starts telling Jesus’ story.

Not going to lie this concept is bizarre. A genealogy is obviously not a literary device, but a factual representation of history. I don’t see how an author could alter a statement of fact without diminishing the credibility of his work. Then I find it equally odd that translators obviously viewed this as an error or they wouldn’t have corrected it in the English version.

What makes you so sure genealogies are never used as literary devices?

I checked interlinear Greek New Testament and Strong’s concordance. In both cases it is Asa and Amon and not ASAPH and AMOS. I am not sure what Greek New Testament you are reading.

Hi, Rabindra! I’m using the NA 27 Greek New Testament via Logos Bible Software.

If your interlinear Bible is like mine, the English word is really a paraphrase to create agreement with the OT. Just look at the Greek word above it and check the letters and you will probably see that in Greek, the words really are Asaph and Amos just as Jeffrey says.

So what you’re saying is that King Manasseh’s son was Amos the prophet not evil King Amon?

Absolutely not.

King Manasseh’s son was King Amon.

Amos was a prophet.

Matthew used Amos’ name instead of Amon’s.

Matthew was being clever and making a theological point for his audience.

You are saying Matthew lied. If he changed the name then he lied.

A lie is told (or written) with the intent to deceive, and Matthew’s not trying to fool anybody. Any Christian (or Jew) of Matthew’s time with access to the Old Testament could have pulled out the books of Chronicles and demonstrated that Matthew’s genealogy doesn’t line up with the Chronicler’s: some generations are clipped out to make three neat stacks of 14, and a few different names are used. If that were written to deceive people, I would think the church would have taken issue with that.

Matthew is introducing his gospel, and he uses an altered genealogy to do so. And that’s not a new take: the church has known about this and been OK with this since the book was written.

Suzanne, I think it’s more like Matthew publicly (because his Jewish audience would catch this right away) REJECTED these evil descendants, instead marking Jesus as coming from a family line of those who praise God (Asaph the psalmist) and who speak for him (Amos the prophet). The idea of being a spiritual descendant or coming “in the spirit of” notable figures in biblical history was accepted, and as important or more than physical line of descent. Jesus wasn’t coming as a king who could get away with murder and worse – he was coming to bring glory to God like a psalmist, and to serve every function of a true prophet. Even though I am not a Jew, I am familiar with the Old Testament, so when I read through the genealogy before I ever learned what this page is teaching, those names stuck out to me, too. I had read OT genealogies, and I could go back to check again, but I didn’t have to go back to check out the names of Asaph and Amos. It took me aback to run into those names, but when I thought about it, I knew what they meant. Righteousness and power… Jesus came from that!

On point 4, I think you are in error. Amon was the son of King Manasseh, and became king at age 22. He did the same evil things that his father did and he was assassinated in his palace. 2 Kings 21:18-26.

Amon was the son of Manasseh—that’s the king I’m referring to. However, the Greek text of Matthew doesn’t say “Amon,” it says “Amos.”

Amos was a completely different character in the Bible: he’s credited with writing the book named after him. Matthew knows this and so would his original readers. The English translators “fixed” the text to read with the same names we’d find in the Old Testament.

Another interpretation of the 14’s…. The numerical value of David is 14. So it’s like Matthew said, ” David, David, David.” For Matthew, who presented Jesus as the Messiah King, affirming Jesus as the Son of David was a big deal.

Magnificent, impressive awe-inspiring study!!! I like your break down of the scriptures, you are definitely one of the few who study, a workman rightly dividing the word of truth.

Hosea 4:6 My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge: because thou hast rejected knowledge, I will also reject thee, that thou shalt be no priest to me: seeing thou hast forgotten the law of thy God, I will also forget thy children.

Without studying there is no KNOWLEDGE! There was no English language 2000 years ago. Understanding what words meant to the Hebrews and Greeks required a sincere sacrifice of study time.

The word “SIGN” is used in the KJB OT 46 times and 30 times in the NT. That is a total of 76!

Chosen is another word found 30 times in the NT. Jesus was 30 yrs of age when he started his ministry.

If you don’t look up the meaning of “sign” you will not have knowledge and without knowledge you will be confused. 1 Corinthians 14:33 For God is not the author of confusion, but of peace, as in all churches of the saints.

Those with a eye to see and a hear to hear will understand this. The mirror image of Hosea 4:6 is Deuteronomy 6:4 Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord:

Sign is found 46 times in OT. Their is only (1) God and: It is he that sitteth upon the circle (O) of the earth, In the language of short hand you could write that as (10)

Thank you Jeffrey, your studies are a God Send!

There was a comment I just read by Glen Manning: Those with a eye to see and a hear to hear will understand this. The mirror image of Hosea 4:6 is Deuteronomy 6:4 Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord:

How is Hosea 4:6 the mirror image of Deut.6:4? Please clarify.

Thanks, Henry

Thanks for this! Last year, when doing a Bible study with my neighbors, we discussed this genealogy and my neighbor who is Jewish decided to look up the number 14 in one of her favorite websites on Jewish numerology. I have no idea how old these views on the meanings behind numbers are, and I wouldn’t put any stock in it myself, however, it was an enormous testimony to my neighbor as she looked it up and found that the meaning behind the 14th letter, nun, is “The Messiah – Heir to the Throne” or “Mashiach ben David.” I told her that the theme of Matthew actually IS “Messiah the King.” It was quite exciting! At the same time, it means “bent over servant” because of the shape of the letter “nun”.

There’s a good deal of observation about the connection between David and the number 14 here. The three Hebrew letters that you use to spell David (דוד) “add up” to 14, given that in the Hebrew alphabet, the “ד” is the fourth letter, and the “ו” is the sixth. So:

“ד” + “ד” + “ו”

would be,

6 + 4 + 4 = 14

Ta-da!

Only reason that’s not in the video is that it didn’t feel quite enough like Old Testament knowledge so much as general Hebrew knowledge. ;-)