Matthias the Apostle was one of the twelve main disciples of Jesus Christ. He’s the only disciple who wasn’t personally called by Jesus. Instead, the other disciples chose him to replace Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus and died shortly after Jesus was crucified.

Matthias is only mentioned by name in Acts 1:23 and Acts 1:26, but from that point on, whenever the Twelve apostles are referred to collectively, he’s with them. Beyond these two mentions in Acts, the New Testament tells us nothing about him. However, we do know that he met the requirements Peter established for replacing Judas: he’d followed Jesus since his baptism by John the Baptist, and he witnessed Jesus’ ascension to heaven (Acts 1:21-22).

As was the case with several of the more obscure disciples, the early church was often confused about Matthias’ identity, which makes it difficult for us to learn much more about him. Some argued he was the same person as Nathanael or Zaccheus, and they even mixed him up with Matthew. There are also apocryphal texts which claimed to give us an account of Matthias’ ministry, and various traditions emerged surrounding his missionary journeys and his death.

Much of what we “know” about Matthias is actually rooted in legend or speculation. So who was Matthias the Apostle really? Let’s walk through the basics and dig into the unknowns.

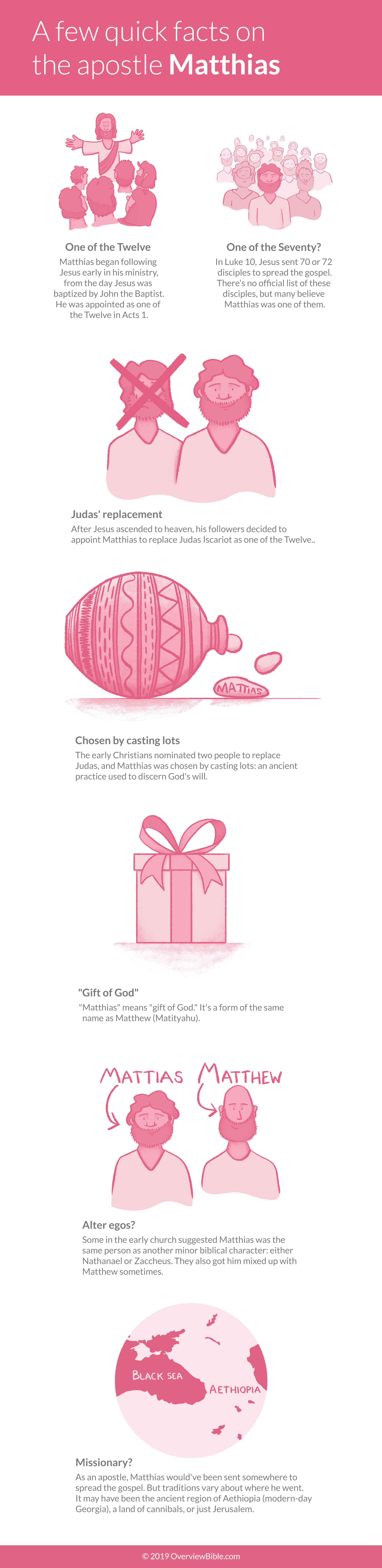

First, here’s a quick look at Matthias the Apostle.

Who was Matthias?

We don’t read any mention of Matthias until after Jesus ascends to heaven in Acts 1, but we learn in Acts 1:12–26 that Matthias had been there the whole time. And once he joined the ranks of the Twelve, he likely took on a more important role in the early church (we just don’t know much about what that entailed).

Here’s what we do know.

One of the Twelve

Matthias began following Jesus early in his ministry, from the day Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist. He wasn’t a member of Jesus’ inner circle, like the other members of the Twelve, but he did live with Jesus and the apostles, witnessing Jesus’ miracles and teachings. Before the apostles chose Matthias, Peter declared:

“Therefore it is necessary to choose one of the men who have been with us the whole time the Lord Jesus was living among us, beginning from John’s baptism to the time when Jesus was taken up from us. For one of these must become a witness with us of his resurrection.” —Acts 1:21–22

As one of the Twelve, Matthias would have been among the first Christians to receive the Holy Spirit, and he played an important role in launching the movement which became the world’s largest religion.

Since Matthias was with Jesus from the beginning, and clearly was well-known among the disciples (the 120 or so believers mentioned in Acts 1:15 nominated him, after all), this has led some to speculate that Matthias must’ve been among the 70 (or 72) apostles Jesus sent out in Luke 10.

One of the Seventy?

In the Gospel of Luke, we learn that Jesus appointed 70 (or depending on the manuscript, 72) disciples to spread the gospel in pairs of two:

“After this the Lord appointed seventy-two others and sent them two by two ahead of him to every town and place where he was about to go.” —Luke 10:1

These believers were sent out to test the hospitality of the towns Jesus was heading to and gauge their receptiveness to the gospel. They were given the authority to heal the sick and cast out demons (Luke 10:9, Luke 10:17), and they preached the gospel.

Interestingly, Luke is the only gospel writer to mention them, and he doesn’t tell us their names (that’d be about as thrilling to read as Matthew’s genealogy). While that saves us from slogging through seventy (or seventy-two) names of people we’d likely never read about again, it also, unfortunately, prevents us from learning about these important early followers of Jesus, who were probably leaders in the first-century church.

An ancient text which claimed to be written by Hippolytus of Rome documented the names of the seventy apostles—nearly all of whom allegedly became bishops—including Matthias, “who supplied the vacant place in the number of the twelve apostles.” While many in the early church believed Matthias was among the seventy, and it’s certainly possible, this list is usually attributed to Pseudo-Hippolytus, because it’s likely pseudepigrapha—writing that falsely claimed to be written by someone (usually someone well-known and authoritative).

Other lists of the seventy or seventy two don’t include Matthias, and have other discrepancies. And Eusebius of Caesaria—the father of church history who wrote in the fourth century—claimed that there was no official list of the seventy:

“The names of the apostles of our Saviour are known to everyone from the Gospels. But there exists no catalogue of the seventy disciples.” —Church History

Eusebius does, however, mention that most people believed Matthias was one of them. And as a prominent early follower of Christ (Acts 1:21–22), it wouldn’t be surprising if he was.

Judas’ replacement

In the beginning of Acts 1, Jesus ascends to heaven and tells his followers:

“Do not leave Jerusalem, but wait for the gift my Father promised, which you have heard me speak about. For John baptized with water, but in a few days you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.”

They didn’t know what to do. They stood there watching Jesus, and two angels appear to basically tell them, “What are you all standing around for?!” (Acts 1:10–11).

Jesus’ ascension killed their momentum. Their only instructions were to “wait,” and they had several days before anything else was supposed to happen.

But in the meantime, Peter realized there was something they could do.

Judas Iscariot betrayed Jesus and then died (either by hanging himself or falling in a field), which made the Twelve into the Eleven. The number twelve carried deep spiritual significance to the Israelites. It represented completion and the twelve tribes of Israel. And since the Christian movement was meant to be the “true Israel,” Peter felt the apostles needed to appoint a new twelfth leader.

Peter stood up and said:

“‘Brothers and sisters, the Scripture had to be fulfilled in which the Holy Spirit spoke long ago through David concerning Judas, who served as guide for those who arrested Jesus. He was one of our number and shared in our ministry.”

(With the payment he received for his wickedness, Judas bought a field; there he fell headlong, his body burst open and all his intestines spilled out. Everyone in Jerusalem heard about this, so they called that field in their language Akeldama, that is, Field of Blood.)

‘For,’ said Peter, ‘it is written in the Book of Psalms:

‘“May his place be deserted;

let there be no one to dwell in it,”

and,

‘“May another take his place of leadership.”

‘Therefore it is necessary to choose one of the men who have been with us the whole time the Lord Jesus was living among us, beginning from John’s baptism to the time when Jesus was taken up from us. For one of these must become a witness with us of his resurrection.’” —Acts 1:12–22

And that’s how Matthias became part of the Twelve.

Since Paul was later called directly by Jesus and made an apostle to the Gentiles, some speculate that Matthias’ appointment was premature, and more a result of Peter’s ambition (or restlessness) than God’s design.

But others argue that the way the apostles chose Matthias actually reflects that God had already chosen him.

Chosen by casting lots

Luke tells us that Matthias was chosen by “casting lots”:

“Then they cast lots, and the lot fell to Matthias; so he was added to the eleven apostles.” —Acts 1:26

Scholars disagree about what exactly is meant by “cast lots” here. It could mean they voted. Or they put each candidate’s name on rocks, put them in a pot, and shook it until one came out. (That’s what casting lots entailed in the Old Testament.) It’s also possible that “cast lots” was simply used here to communicate that the community chose Matthias, and the exact means by which they chose him wasn’t important.

In the Old Testament, casting lots was seen as a method of getting answers from God. In 1 Samuel 14, for example, Saul used lots to ask God who had sinned, and discovered that his son Jonathan had led his soldiers astray, first by breaking an oath Saul made which cursed anyone who ate before evening (1 Samuel 14:24, 1 Samuel 14:27), and then by leading the soldiers to break God’s law by eating food that was always forbidden (1 Samuel 14:32-33):

“Then Saul prayed to the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Why have you not answered your servant today? If the fault is in me or my son Jonathan, respond with Urim, but if the men of Israel are at fault, respond with Thummim.’ Jonathan and Saul were taken by lot, and the men were cleared. Saul said, ‘Cast the lot between me and Jonathan my son.’ And Jonathan was taken.

Then Saul said to Jonathan, ‘Tell me what you have done.’

So Jonathan told him, “I tasted a little honey with the end of my staff. And now I must die!’” —1 Samuel 14:41–43

It sounds pretty silly out of context. But Jonathan also basically said it was the food in their bodies and not the favor of God which made them victorious (1 Samuel 14:29–30).

So whatever Luke meant by “cast lots,” the process was rooted in Scripture, and intended to learn what God’s choice was, not for the disciples to make a choice of their own. And the distinction is important, because some argue that by choosing Matthias, the apostles were interfering with God’s plan to make Paul the twelfth member of the Twelve. (More on that later.)

“Gift of God”

Matthias is a diminutive form of the same name Hebrew as Matthew: Matityahu. They both mean “gift of God.” Since Matthias and Matthew were notable biblical figures and their names were forms of the same name, it’s not surprising that some early church traditions mixed them up.

Professor A.F. Walls notes in The New Bible Dictionary:

“His name was often confounded with that of Matthew, a process doubtless encouraged by the Gnostic groups who claimed secret traditions from him . . .”

Alter egos?

In addition to confusing him with Matthew the Apostle, some in the early church assumed Matthias was another name for an obscure New Testament figure. It was common for first-century people (and biblical characters) to have multiple names they were known by. The Apostle Peter, for example, was known as Simon, Simon Peter, and Peter.

Some in the church believed Matthias was really Nathanael, a friend of Philip who is only mentioned in the Gospel of John (John 1:43–51, John 21:2). Nathanael was one of the first called, but not a member of the Twelve. (Unless you assume he was also called Bartholomew, which many Christians still do today.)

Others confused him with Zaccheus, the infamously short and shrewd tax collector (Luke 19:1-10). How in the world did that happen? Professor Walls suggests:

“The early identification of Matthias with Zacchaeus (Clement, Strom. 4. 6) may also arise from confusion with Matthew the tax-collector. The substitution of ‘Tholomaeus’ in the Old Syriac of Acts 1 is harder to understand.”

Missionary?

As one of the Twelve, Matthias was an apostle, which meant he was charged with preaching the gospel and helping it spread throughout the known world. The word we translate as apostle (apostolos) literally means “one who is sent,” and all of the apostles were sent somewhere.

But where exactly Matthias went depends on which tradition you follow.

Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos was a fourteenth century historian who built on the work of his predecessors and had access to important texts that no longer exist. He claimed Matthias preached in Judea, then Aethiopia (modern-day Georgia).

A surviving copy of Acts of Andrew and Matthias claims he went to an unnamed land of cannibals:

“About that time all the apostles had come together to the same place, and shared among themselves the countries, casting lots, in order that each might go away into the part that had fallen to him. By lot, then, it fell to Matthias to set out to the country of the man-eaters.”

Other traditions suggest Matthias preached in Jerusalem.

Was Paul supposed to replace Judas?

Some Christians believe Matthias never should’ve been appointed as one of the Twelve, and that since Jesus personally called Paul, he was clearly meant to be the twelfth apostle who would “complete” the group.

The main counterargument is that the apostles specifically prayed for God to reveal his choice:

“Lord, you know everyone’s heart. Show us which of these two you have chosen to take over this apostolic ministry, which Judas left to go where he belongs.” —Acts 1:24

The process of casting lots was always intended to learn what God had already decided, not to provide a means for humans to make a choice. It was like the classic trope of “letting fate decide,” but throughout Israel’s history, God used the process of casting lots to reveal hidden knowledge (as was the case in 1 Samuel 14).

Pastor Thomas Martin argues in Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary that whatever “casting lots” meant here, the point was that God, not the apostles, chose Matthias:

“In any event the story makes it clear that God selected Matthias to fill Judas’ vacancy. This causes speculations that Paul was meant to be the twelfth apostle and that Peter and the early community overstepped their authority in appointing Matthias to appear polemical.”

But that argument seems to ignore the human element that was at play here: Peter assumed it was their duty to start the process of replacing Judas Iscariot, and he and the believers chose two people before asking God to reveal . . . his choice between their two nominees. It wasn’t like they cast lots between all 120 believers who were present, and they didn’t start by asking God, “Hey, do you have a plan, or should we get the ball rolling?”

Assuming God had intended for Paul to replace Judas, giving us a group of 12 who were all personally called by Jesus, Peter left no room for God to do that without some miraculous intervention.

It’s possible to argue Matthias shouldn’t have been appointed one of the Twelve, but in the end it doesn’t really matter, because he was. And as a result, he played a larger role in helping the gospel spread, and by all appearances, it had no impact on Paul’s ability to do ministry or to be considered an apostle.

How did Matthias die?

Similar to Matthias’ ministry, the nature of his death varies. Some traditions claim he was stoned at the end of his ministry to cannibals in Aethiopia (Georgia). Another that he was stoned by Jews in Jerusalem and then beheaded. Hippolytus of Rome records that he died in Jerusalem of old age.

The Gospel of Matthias

The Gospel of Matthias is a lost text which claims to be written by Matthias. The early church had mixed opinions on its authenticity, and we only know about it from the writings of others.

Clement of Alexandria quotes it while describing a heretical sect of Christianity known as the Nicolaitanes—whose teachings John the Revelator claims Jesus hated (Revelation 2:6)—telling us it says, “we must combat our flesh, set no value upon it, and concede to it nothing that can flatter it, but rather increase the growth of our soul by faith and knowledge”.

Eusebius claimed it was written by heretics as well. But without the text itself, it’s impossible to say what value it may have had.

Acts of Andrew and Matthias

The Acts of Andrew and Matthias is a Gnostic text which contains a legendary account of Andrew and Matthias.

In it, Matthias is sent to preach the gospel in a land of cannibals, where the locals remove his eyes (as was their custom), give him a poison that is supposed to make him lose his mind (it doesn’t work), and throw him in prison with others who are waiting to be killed and presumably eaten.

Jesus appears to Matthias in prison to restore his sight and encourage him. Matthias closes his eyes whenever the guards come, so they won’t know he got them back.

Three days before the cannibals kill him (they always wait 30 days before killing their prisoners), Jesus appears to Andrew and sends him on an emergency rescue mission to save Matthias.

Andrew gets on a boat which happens to be crewed by Jesus (whom Andrew doesn’t recognize) and two angels. During their voyage, Jesus passes the time by asking Andrew about . . . Jesus. Eventually, he urges Andrew to share a miracle not recorded in the gospels. So Andrew tells Jesus about the time Jesus made a sphinx statue come to life and then summoned the twelve patriarchs of Israel because some priests asked “Why should we believe him?”

When he arrives at the city of the cannibals, Andrew is invisible to them. He approaches the prison and prays, and the guards all die. Then he makes the sign of the cross, the gate opens, and he walks in and frees Matthias. Together, they restore sight to the blind, free them from the spell of the poison, and release all 319 prisoners. Andrew commands a cloud to come whisk away Matthias.

From there, the legend turns into a showdown between Andrew and Satan. Andrew continually prevents the cannibals from eating anyone. They capture him, and try and fail to kill him by repeatedly dragging him through the street. He commands a statue to spew acid water into the city and a wall of flame prevents them from escaping. A lot of them die. Then the people repent, Andrew resurrects the people who died, and they build a church.

There’s a lot going on in Acts of Andrew and Matthias, but it doesn’t give us anything usable about Matthias.

The backup apostle

The Bible tells us almost nothing about Matthias. But what we do know is that he’d been following Jesus from the beginning—despite not receiving a personal invitation, like the original members of the Twelve. And whether Matthias being an apostle was God’s design or Peter’s, he became an integral leader in the first-century church, and played an important role in spreading the gospel throughout the world.

Friend, concerning your interpretation of verse 18, there is an error. We need to let the bible interpret the Bible. You use good sense when you intrepret it, but Scripture proves you wrong. Look at Matthew 27:5-10. It tells us what money was used to buy the field and when it was bought. Matthew even gives reference to Zechariah 11:13.